Ad Astra: Review

Hundreds of movies tackle the question of whether we are alone in this universe. Ad Astra plays on that question by never revealing if that life has been found, as doing so would defeat the dramatic point. In fact, Ad Astra shows that our greatest conflict is not from outer space, evil geniuses, or militaristic powers ruling with an iron fist. Instead, it is the void within ourselves.

Hundreds of movies tackle the question of whether we are alone in this universe. Ad Astra plays on that question by never revealing if that life has been found, as doing so would defeat the dramatic point. In fact, Ad Astra shows that our greatest conflict is not from outer space, evil geniuses, or militaristic powers ruling with an iron fist. Instead, it is the void within ourselves.

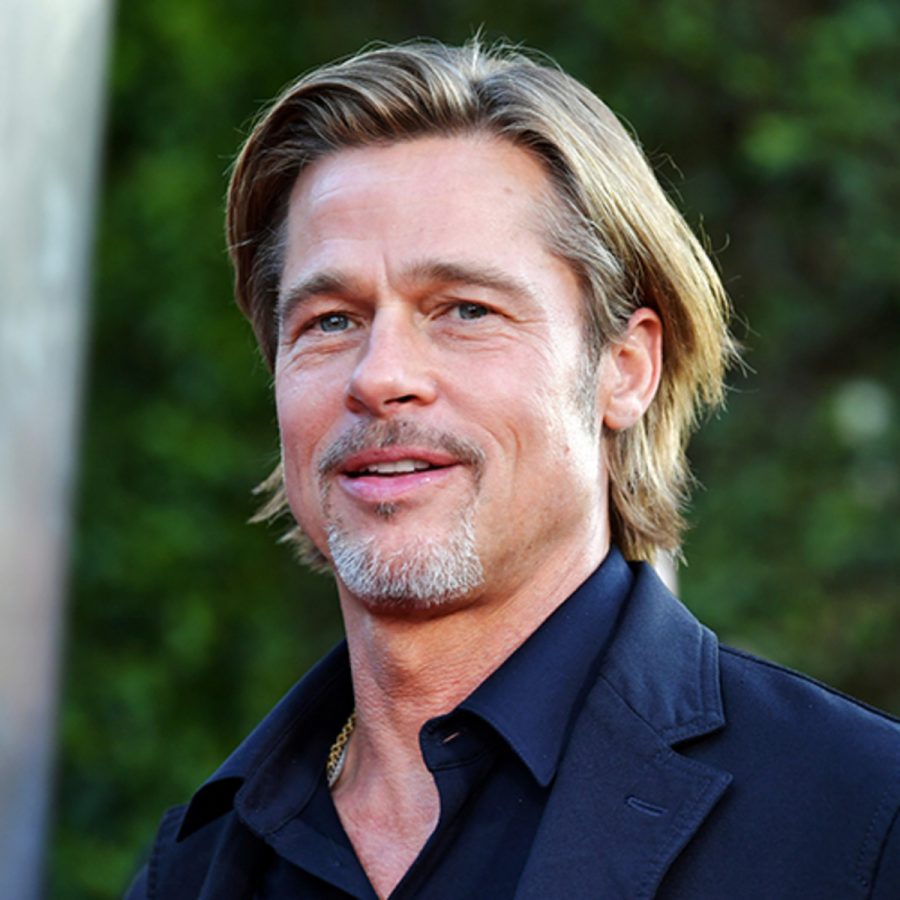

Roy McBride (a stellar Brad Pitt), comes from veritable astronaut royalty. His father, Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), was part of the first team to lead a manned expedition to the outer solar system in humanity’s search for intelligent life. His absence left a deep void in Roy. Roy festers and feeds on it; it’s what makes him such a good astronaut. In the film he is famed for lacking emotion — his pulse never exceeds 80 bpm, even when falling Gravity-esque from space to the ground with metal fragments spinning to the earth alongside him. That same void, however, alienates Roy from human connection, even from his own wife. This ties into the main point of the movie: Roy’s fear of becoming his father: of becoming the same uncaring, distant, even hateful person.

After the opening scenes, in which Roy is nearly killed after falling off the International Space Antenna, he finds out that what caused his fall was an energy surge that affected people all over the solar system. Roy soon finds out, to his well-portrayed surprise, that Clifford is alive and is causing these massive, civilization-endangering surges. And so Roy is sent to the moon, and then to Mars, where he sends a message to his father hoping that his father-son connection will coerce his dad to respond. Roy is instructed to leave Mars, not knowing whether he successfully contacted Clifford, so he commandeers another rocket to find his father for himself.

Watching the film, I immediately noticed the beautiful cinematography. The opening scene is beautiful; a simple wide shot, going from gentle lens flares from the bare sunlight of space to the glowing Blue Marble itself, Earth. The wide, sweeping shots of space; close-ups of Roy’s blank, then conflicted face; and dizzying scenes of cosmic distress, hold nothing back. From the muted tones of Earth to the deep blues of commercial space travel; harsh whites and blacks of the moon’s surface; soundless chaos of a Mad Max-style space-buggy chase; somber orange-red of Mars and the bright, worrying blues of Neptune’s orbit; even the weakening, distortion and strength of the Sun’s rays as Roy grows closer to his father; every shot is deliberate and placed, colors painstakingly chosen, like the matte paintings of years past. Like its spiritual relative 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ad Astra is a spectacle to behold.

Then there’s the depressing take on space. Ad Astra is neither a dystopia nor a utopia; not Alien, but not Star Trek either. While we choose to look beyond the Solar System in search of life, while we do so, Ad Astra says, life, in the form of pure capitalism, moves on at home. For example, take the moment when Roy takes a Virgin Galactic flight to the moon, quietly asking for a pillow and blanket for $125. In deep contrast to the stark grey isolation of the Pan Am flight in 2001, this interaction seems normal. The familiar feeling of an airplane walkway, soft voice of a flight attendant, even the same soothing blue lighting makes it seem that Roy is traveling across the world rather than across space. Even zero-G food looks presentable. This is a world in which spaceflight has become as common as air travel. Upon entering the moon base, which looks suspiciously like a New York Subway Station, we see prominent signs for common companies. Subways, Hudson’s, even an Applebees. A harsh blow compared to 2001’s portrayal of clean, postmodern space — and even this movie’s earlier cleanliness of Earth’s upper atmosphere — Ad Astra shows that even the wonders of the moon aren’t safe from the reach of corporate magnates.

Finally, almost forcefully, we recognize Roy McBride’s internal struggle. Throughout the movie he comments on his situation through a voiceover, remarking on how his training and compartmentalization has led to his becoming more and more like his father. Roy fears turning into someone who endangers human civilization, someone who endangered him. The film follows his journey beyond this fear. Roy realizes his father’s mistakes and vows not to follow them. His own father neglected him in favor of trying to find extraterrestrial life, something that wasn’t there, then desperately tried to justify his abandonment. Roy realizes this, choosing to instead “rely on those closest to me,” sharing “their burdens, as they share mine.” He chooses to “live and love.”

Ad Astra played in theaters starting in September 20th, 2019. If you get the chance to see it in IMAX, do it.