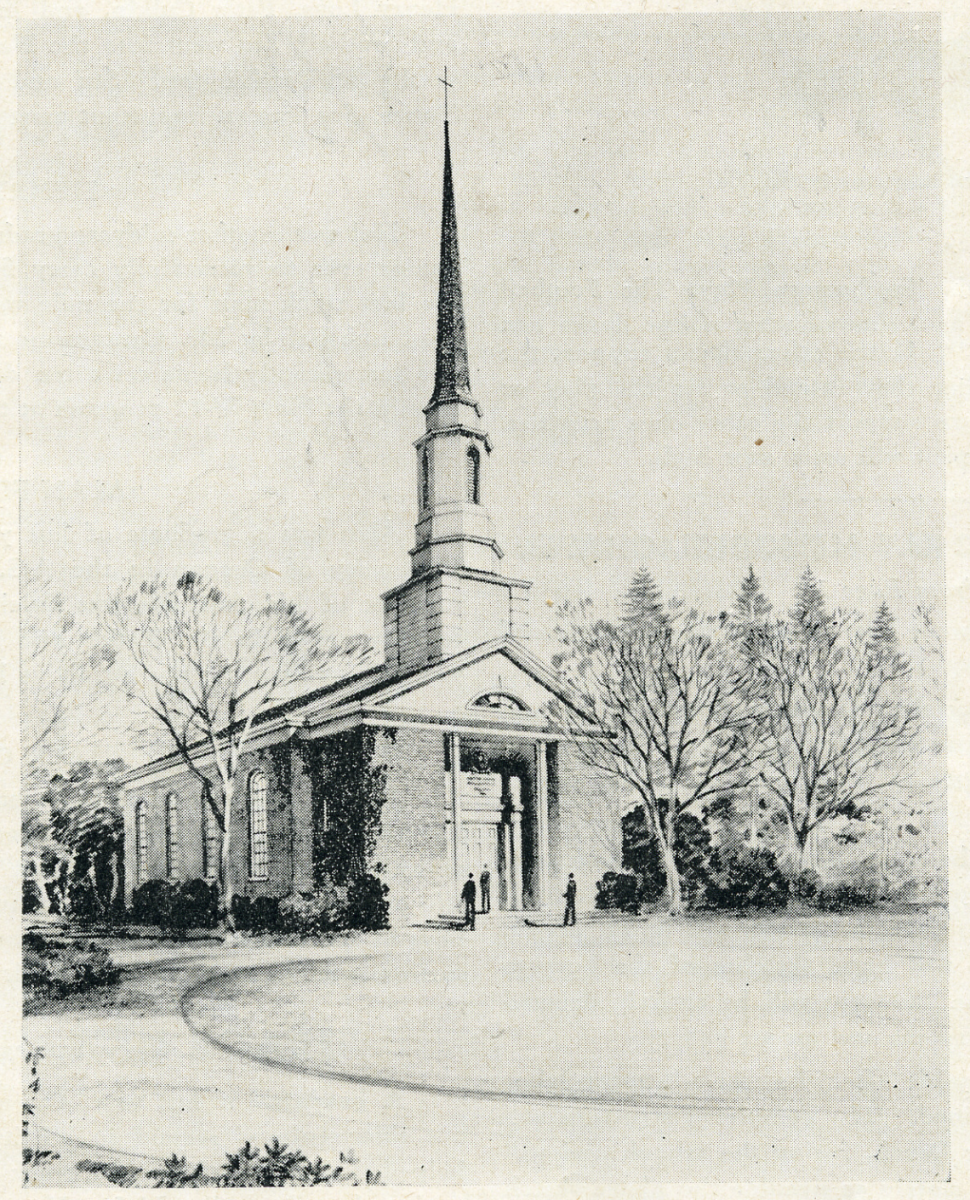

Enter the foyer of McKay chapel, and you will find a black and gold plaque affixed unobtrusively to the wall. Inscribed in bronze metal: “Theodore Aiken McKay Memorial Chapel, built in 1951.” A gift of the McKay family, parents, and friends of the fallen soldiers, the chapel stands in solemn remembrance of thirteen Lakeside alumni who tragically lost their lives in World War II. And so, as Veteran’s Day approaches, let us contemplate the stories of Theodore Aiken McKay, Robert Huntington, and Harold Everett Dupar.

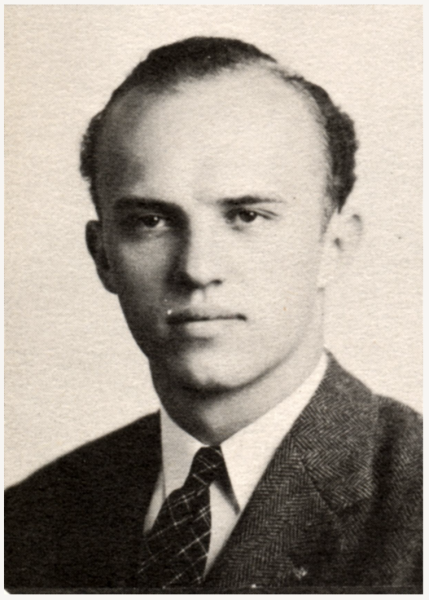

Theodore Aiken (“Ted”) McKay ’38 was a member of the Student Court, Athletic Committee, and head of the Entertainment Committee. Aside from working in the Lakeside community, he racked up an impressive amount of extracurriculars: wrestling, playing quarterback, captaining the football team, and boxing. As organizer of the 1938 Smoker, a father-son boxing event, he managed to assemble over 600 attendees. He was then unanimously voted winner of the tournament, as he “flattened Gallagher in the second round,” (Tatler, June 10, 1938) knocking him out, and emerging victorious. He attended the University of Washington, graduating in the spring of ’42 and marrying Gloria Taylor of Everett. Their move to the east coast was sadly interrupted when McKay was called into duty the same year. He was killed in Guam in 1944.

Theodore Aiken (“Ted”) McKay ’38 was a member of the Student Court, Athletic Committee, and head of the Entertainment Committee. Aside from working in the Lakeside community, he racked up an impressive amount of extracurriculars: wrestling, playing quarterback, captaining the football team, and boxing. As organizer of the 1938 Smoker, a father-son boxing event, he managed to assemble over 600 attendees. He was then unanimously voted winner of the tournament, as he “flattened Gallagher in the second round,” (Tatler, June 10, 1938) knocking him out, and emerging victorious. He attended the University of Washington, graduating in the spring of ’42 and marrying Gloria Taylor of Everett. Their move to the east coast was sadly interrupted when McKay was called into duty the same year. He was killed in Guam in 1944.

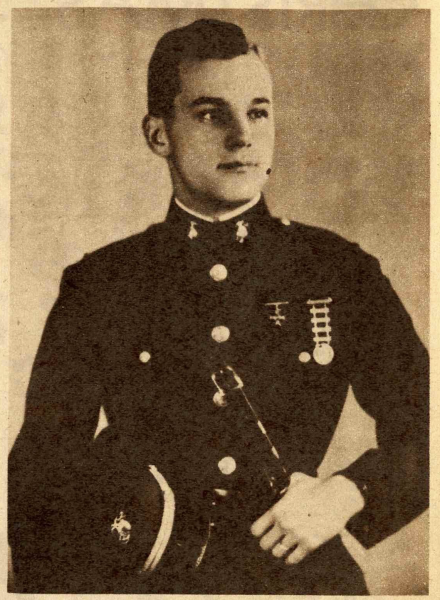

Robert (“King”) Huntington ’40 was a member of the Tatler staff and, like McKay, played football. One of his classmates, Edward C. Larson, described him in his memoir Spear Carrier in a Backwater War as “a rugged kid, a senior, and one of the stalwarts of the team.” Despite being new to the school and a self-described “terrible football player,” Larson recalls that “Bob always treated me with kindness and made me feel a part of the team … it was a brand of kindness that a teenage kid never forgets.” Huntington enlisted in the Navy in April 1941, where he volunteered to work in the torpedo planes — one of the deadliest divisions available. “Throughout his work at Lakeside, King showed character, ability, and willingness to fight against odds,” master’s notations remark of his character — and fight against the odds he did. As a rear gunner in a torpedo plane, Huntington battled tooth and nail amidst immense anti-aircraft barrage and opposition, all without fighter support and insufficient fuel. At 21, he was a part of Torpedo Squadron 8, who gave their lives in the Battle of Midway, June 4, 1942, receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement and heroism. The USS Robert K. Huntington (DD-781), an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, was named in his honor and earned two battle stars for service in Vietnam.

Robert (“King”) Huntington ’40 was a member of the Tatler staff and, like McKay, played football. One of his classmates, Edward C. Larson, described him in his memoir Spear Carrier in a Backwater War as “a rugged kid, a senior, and one of the stalwarts of the team.” Despite being new to the school and a self-described “terrible football player,” Larson recalls that “Bob always treated me with kindness and made me feel a part of the team … it was a brand of kindness that a teenage kid never forgets.” Huntington enlisted in the Navy in April 1941, where he volunteered to work in the torpedo planes — one of the deadliest divisions available. “Throughout his work at Lakeside, King showed character, ability, and willingness to fight against odds,” master’s notations remark of his character — and fight against the odds he did. As a rear gunner in a torpedo plane, Huntington battled tooth and nail amidst immense anti-aircraft barrage and opposition, all without fighter support and insufficient fuel. At 21, he was a part of Torpedo Squadron 8, who gave their lives in the Battle of Midway, June 4, 1942, receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement and heroism. The USS Robert K. Huntington (DD-781), an Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer, was named in his honor and earned two battle stars for service in Vietnam.

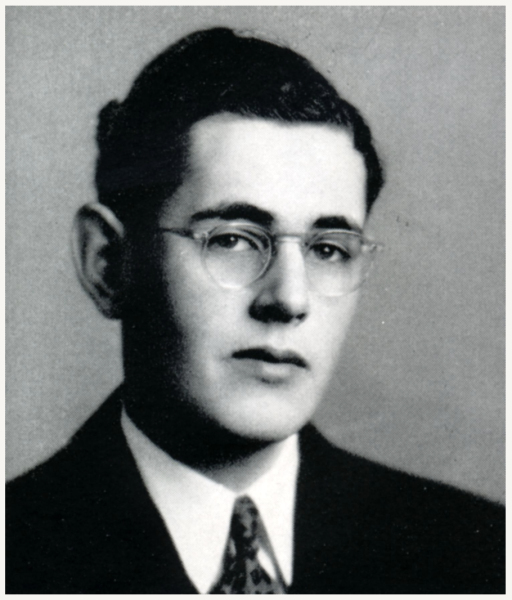

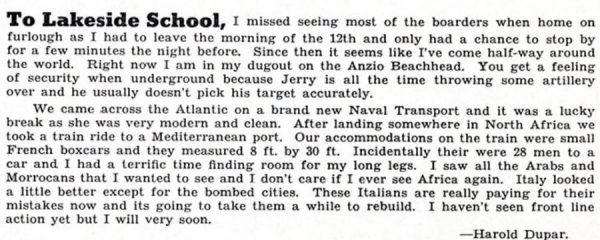

Harold Everett Dupar ’43 served as manager of Numidian, Tatler, and still managed to find time to be a three season athlete — which, like today, is an impressive feat. He was known to be conscientious and collegial. He had scarcely attended college before he left to join the army and, after six months of training, was shipped overseas. During his deployment, he sent letters home, some of which were printed in the Tatler. His messages give a fascinating, if sorrowful, window into his wartime experience. In one of the letters, sent from Fort Riley, Texas, he writes, “We also have had a lot of bayonet drill, dirty fighting and of course no end of dismounted drill.” He continues to say, “We spent two weeks learning to march. The heat was torrid, and every day about twenty men passed out.” Another letter posted to Tatler was sent shortly after his arrival at Anzio, and reads, “Since then it seems like I’ve come half-way around the world. Right now I am in my dugout on the Anzio Beachhead. You get a feeling of security when underground because Jerry* is all the time throwing some artillery over and he usually doesn’t pick his target accurately.” It was the last letter he ever sent.

Harold Everett Dupar ’43 served as manager of Numidian, Tatler, and still managed to find time to be a three season athlete — which, like today, is an impressive feat. He was known to be conscientious and collegial. He had scarcely attended college before he left to join the army and, after six months of training, was shipped overseas. During his deployment, he sent letters home, some of which were printed in the Tatler. His messages give a fascinating, if sorrowful, window into his wartime experience. In one of the letters, sent from Fort Riley, Texas, he writes, “We also have had a lot of bayonet drill, dirty fighting and of course no end of dismounted drill.” He continues to say, “We spent two weeks learning to march. The heat was torrid, and every day about twenty men passed out.” Another letter posted to Tatler was sent shortly after his arrival at Anzio, and reads, “Since then it seems like I’ve come half-way around the world. Right now I am in my dugout on the Anzio Beachhead. You get a feeling of security when underground because Jerry* is all the time throwing some artillery over and he usually doesn’t pick his target accurately.” It was the last letter he ever sent.

*During WWII, civilians and soldiers of the allied nations referred to the Germans by the nickname ‘Jerry,’ which is also the basis for the word ‘jerrycan’—a type of fuel container made from steel.

One of the school’s youngest victims of the war, Harold Everett Dupar was killed at age nineteen in Anzio, Italy, on June 24, 1944. His family gifted an organ to the chapel in his honor, and later contributed two scholarships in his memory.

The stories of these men invite us to not only appreciate their individual tales of valor, but also to acknowledge the shared sacrifice of all thirteen alumni during World War II. McKay Chapel stands as a testament to their memory and a poignant reminder of the impact of war on our community.