Wild Life Epitomizes the Risks of the Single Narrative

In the few months since its release, the documentary Wild Life has already attracted decidedly mixed press. Described by Variety as a “soaring documentary tribute” and labeled by The Washington Post “a galvanizing tale of philanthropy”, no one seems quite certain of what to make of it.

After braving the rainy Saturday afternoon traffic and navigating a maze of parking garages, sky bridges, and mostly deserted bowling alleys, I arrived one weekend in early May in a darkened Cinemark in a mall in Bellevue, the only venue still screening Wild Life. This was a special showing: afterwards, there would be a Q&A session with the film’s co-director, Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi.

First premiering in the South by Southwest Film Festival in March of this year, Wild Life is a documentary following former Patagonia CEO turned full-time conservationist Kris Tompkins and her husband — Doug Tompkins of The North Face — through to the aftermath of his death in 2015. Starting out as entrepreneurs, the two made a new name for themselves in the ’90s when they began purchasing huge swaths of land in Latin America to convert into national parks.

In exploring their personal lives, the film uses Kris’ personal letters and remarkably extensive film documentation of each character’s young life to good effect. It’s also heavy on the element of alpine spectacle one would expect from Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, the comparably environmental husband-wife duo responsible for 2018’s Free Solo.

Although the audience reception at my showing was generally enthusiastic, as the lights came up and she took to the stage, Vasarhelyi seemed to anticipate criticism. Repeatedly, she stressed how hard the film had been to put together — a project eight years in the making — and how wary she had been to go through with it. Yet the only question approaching reproval from the crowd was one about the framing of the conclusion as just that: a conclusion to the larger narrative. Interviewees don’t shy away from the fact that forests across Chile are still shrinking at alarming rates, so where is the pop-up window of ways to get involved, organizations to funnel money into and senators to call? This one Vasarhelyi wasn’t interested in deflecting. Her response was simple: if you want a list, look it up online. There was no call to action because that wasn’t the point of the film.

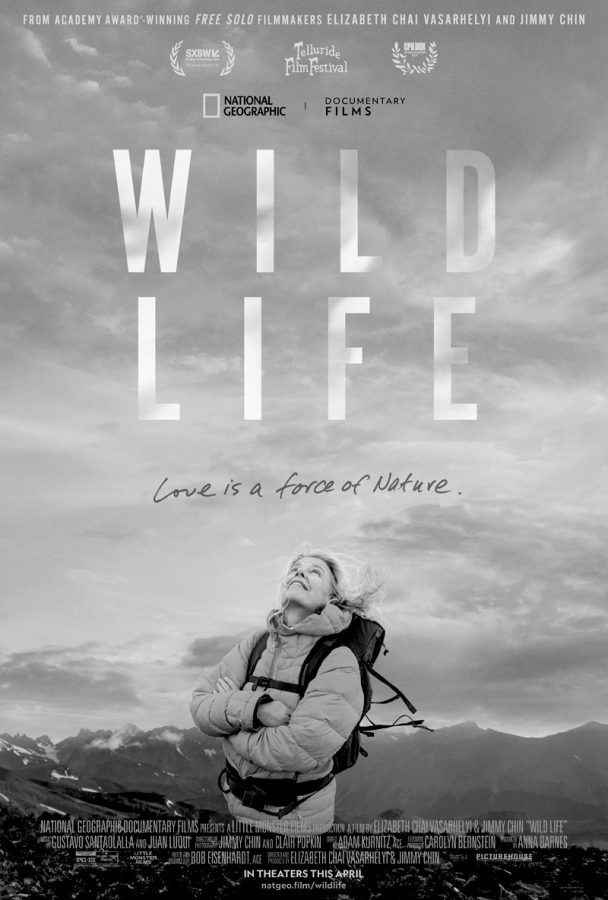

Indeed, the role of the viewer feels minimal in Wild Life. In case the cover’s lone figure and rousing subtitle—“Love is a force of Nature”—weren’t tip-offs to prospective movie goers that afternoon, this is a story deeply grounded in the lives of individuals. It’s natural that the perspective would be limited due to the intended scope of the film. It was very clear in what it set itself up to accomplish and followed through appropriately. Besides, it’s not a movie for children. It’s nonfiction, and it doesn’t need to be prescriptive or weighed down with disclaimers in order to assume it will be watched with an occasionally critical eye.

At least, that’s what I kept reminding myself as I left the theater that evening. Still, I couldn’t shake a creeping sense of unease. In the midst of many more tangibly relevant pieces, one scene kept replaying itself in my mind. It was one where Kris describes how, after completing the first documented ascent of a peak, Doug, in a show of romance worthy of all the swelling strings that could be set to sweeping gorges and jagged logo skylines, planned to name the mountain after her. How many peaks and valleys across America, I wondered, have been named by similarly well intentioned visitors? As much as I wanted to swallow an undoubtedly heartfelt story of passion persevering over economic gain and drive persevering over grief, I was choking on the bone.

And yes, there are of course other sides to this narrative which are generously skipped over for the purposes of Wild Life. We hear from a couple stamp-wielding Chilean politicians, but what about the voiceless presence of the farmers, the miners, the manufacturers being pushed off this land? We hear about the Tompkins’ ambitions to install ecological beekeeping and jam making at the economic core of communities around their parks, but footage of the actual members of said communities — people whose lives might not fit so neatly into one fetishised, economically unimpeded idea of agrarian life — are conspicuously absent.

Thinking about the impact of the area of land they have purchased, it’s also important to remember that a country as slender as Chile is not comparable with the US, where vast parks can be stowed away in the interior without much perceptible effect. At one narrow region, Pumalín National Park fully bisects the country. You can’t drive from one tip to the other without passing through a region marked off with Doug Tompkins’ name.

Ultimately, Wild Life raises questions not just about the ethics of the Tompkins’ work, but also how the voice of the documentarian ought to be used. In my view, the final outcome of this story—nearly 15 million acres of preserved public land across Chile and Argentina—is still a unilaterally positive one. At the end of the day, these people’s intentions and methods don’t really interfere with that. Yet there is favoritism just in the matter of who gets access to the microphone.

The opposition the Tomkinses have met in Chile is not ignored in the film, but it’s not engaged with meaningfully. Instead of real critical voices, we are at various points subjected to a barrage of headlines and TV news clippings, which — while likely reflecting the viewpoint of the Tomkinses accurately — calls into question where the value lies in highlighting a single perspective if it means flattening a complex issue into a matter of the righteous versus their unjustified attackers. It feels especially short-sighted where the film seems to reinforce interviewees’ chidingness of Chilean fear of American intervention — a fear that has been nothing but justified by history.

On a practical level, this is not really a story of neo-colonialism. Rather, it is a story of good intentions, ignorance, and unchecked capitalism in every direction. Wild Life is a technically strong film that takes this and leaves out what are arguably the most thought-provoking angles of storytelling. Although the Saturday afternoon audience was right to withhold their censure, Vasarhelyi was also probably right to expect it. This is a case where the greatest power lay in the hands of the filmmakers, and they have used it to bolster a dominant narrative that questions—and therefore communicates—nothing.

Once Tatler’s least prolific writer, Eliot now contents himself with a calling that lends itself better to procrastination. He also co-edits IMAGO, Lakeside’s...