Tambien La Lluvia: Opinions From the Spanish Classroom

Over the past two years, current Spanish III students have studied important cultural and historical events in Latin America through film, including Augosto Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile and the Bolivian Water Wars: in Spanish II, for example, students watched the movie No, directed by Pablo Larraín, which uncovers the unique advertising techniques used by the “No” campaign to overthrow Pinochet in the 1988 plebiscite. Students who enjoyed this film found that the movie gave a comprehensive and hopeful overview of Pinochet’s fall. The leading actor Gael Garcia Bernal was a favorite for his realistic portrayal of a sought-out advertiser conflicted by the personal and political. The movie also had ongoing relevance to modern political systems and democracy, as many marginalized communities around the world are still underrepresented in government today.

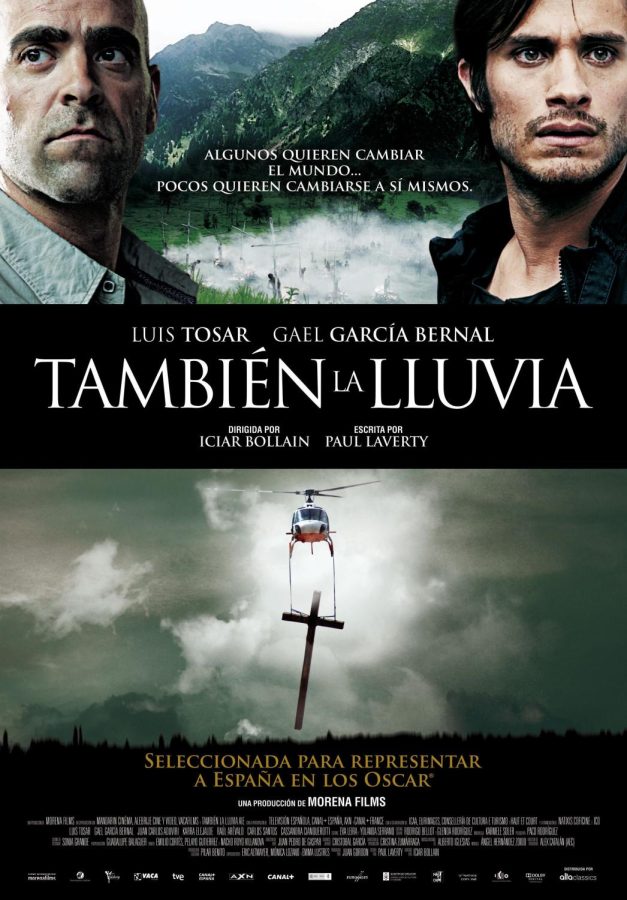

The following year, Spanish III students watched También La Lluvia, directed by Iciar Bollain. The powerful name points to the crux of the film: that Even the Rain has been taken from indegenous people in Latin America. Set in the Bolivian town of Cochabamba in 2000, También La Lluvia tells the story of the protests succeeding water privatization in the country, known as the Bolivian Water Wars. The historical account is shown through the lens of a wealthy, foreign film director working on a movie about colonialism in the country.

Both films were well received by Spanish students, with student ratings ranging between three and five stars. 57% of Spanish III poll respondents preferred También La Lluvia, over No, while 28% of respondents provided a contentious argument on why No was better. An anonymous poll respondent found that “También La Lluvia was a bit abstract in choosing to center on a meta-film but it gets the message across effectively.” Another anonymous student also “appreciated how the film drew parallels between the atrocities committed by Columbus when he arrived and the abuse of indigenous people in modern times.” These intentional connections allowed viewers to draw their own conclusions about the lasting effects of colonialism. By centering the movie on the creation of another film, También La Lluvia explores the arbitrary nature of perspective.

Along with making modern connections to Bolivian colonialism, También La Lluvia also highlighted the consequences of civil unrest and political instability. Scenes in the movie depicted protests by indegenous people, civilian blockades, and the lavish lifestyle of the foreign filmmakers and politicians, demonstrating the experiential disparity that comes with class and nationality differences. The movie also showed government forces maiming civilians, starting fires, and setting bombs off in the streets. Some of these scenes were rather graphic and uncomfortable, but such scenes were important in enhancing viewer’s historical understanding of the Water Wars and other similar political conflicts in Latin America. Avery P. ’24 felt that the film “showed the personal parts of the environment and the consequences, such as the little girl’s injury,” referring to when a young indegenous girl injured her leg during a large protest, losing her ability to walk. Events such as these drew the plot away from the narrative of the in-movie filmmakers, bringing more historically relevant voices to the forefront. Other scenes such as one where Costa, the lead film maker, tries to bribe Daniel, an indigenous actor, into refraining from attending protests, were equally effective in showcasing the foreigners’ dangerous, narrow minded tendencies. One anonymous student stated that “the actors were phenomenal, especially as they had to act on two different levels of inception. Emotions were conveyed very effectively and I was made sufficiently uncomfortable.” Perhaps this, above all, is the central purpose of the film: También La Lluvia allows outsiders, such as ourselves, to better understand our moral obligations to better educate ourselves about how we are inadvertently contributing to the underlying social and political inequities in Latin America.

Unfortunately, by only portraying the outsider perspective of foreign filmmakers, the film lost its connection to the indigenous communities. One anonymous student wished that the movie “went deeper into the struggles of the indigenous people,” while Katherine H. ’24 was disappointed that “the whole focus of the movie was on foreigners experiencing the unrest of communities they had little context or care for, and ultimately through the end of the movie didn’t make much of an effort to learn about.” Katherine H. ’24 also noted that the film failed to develop “a meaningfully reciprocal relationship between the film crew and the indigenous community, leaving the ending feeling like a Deus Ex Machina, and worse, falling into the white savior trope.” Throughout the film, Costa was very inconsiderate of the indigenous actors, paying them unfair wages and asking them to refrain from attending protests with little knowledge of the subject matter. At the end, he had an unexpected change of heart, heroically saving a young indigenous girl before leaving the country. This far-fetched closing, although intended to highlight character development in Costa, led to little resolve. An anonymous student who echoed similar sentiments also called attention to the fact that “the movie demonstrated how an ignorant person can come to understand the hardships many native people experience even if they have not experienced it themselves.” Although Costa and other foreigners in the film recognized indigenous struggles by the end of the film, their self interest overshadowed their desire to improve the situation in Bolivia. This reflection on human nature, although somber in tone, serves as a powerful catapult for fast, large-scale action from outside forces that look beyond victimizing marginalized communities.

Although También La Lluvia primarily focuses on the filmmakers’ perspectives of the Water Wars, the movie still displays indigenous communities and prominent political figures in a nuanced, thought provoking manner. Avery affirms that the movie “showcases different perspectives” and another student felt that the movie was “a good way to be introduced to large historical events in Latin America.” The movie closes when Daniel gives Costa a vial of water, a powerful recurring symbol of livelihood and freedom. Daniel’s generosity provides a nice contrast to the otherwise negative portrayals of human nature throughout the film, inspiring hope, growth, and discovery in the viewers. Mia L. ’24 found that “it took a while for the movie to become more engaging, but the ending was very powerful, making the movie worth watching.” También La Lluvia is targeted to an outside viewer, an audience like ourselves, that must recognize our responsibility to right our historically passive stance in Latin America. With that goal, it is absolutely succeeding.

Tatler’s resident writer and logic puzzle creator, Angelina P., has a knack for CRISPR-Cas9 technology, Spanish television, and Balanchine ballet. When...