Winds of Friendship

The Winds of Friendship sculpture, with Bliss Hall in the background.

Its golden sheen glistening under the pale sun, its four semicircles revolving with the crisp wind, its shadow dancing over the low roof of Allen-Gates: do you know which Lakeside sculpture I am referring to? Brownie points if you know its name (and no, it is neither “that cool spinny thing” nor “the parking lot windmill”).

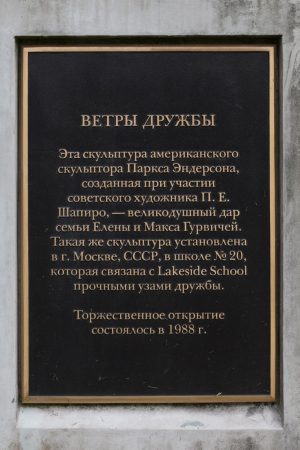

The Winds of Friendship stands proudly for us all to see, yet we—engrossed in our phones and our hurried steps—rarely stop to look past its ambience. It is a fortunate few who have even taken the half-minute to read the plaques at its bottom. This sculpture comes with an inspiring story that fully deserves a more prominent place in Lakeside lore.

The story begins in the late 1970s, as the U.S. and U.S.S.R. were heading into the last decade of the Cold War. It was precisely this period of international tension when Lakeside first established relations with the English specialty school Moscow School No. 20, whose students included children of distinguished Soviet officials. This fortuitous and remarkable connection was forged by former Lakeside trustee Jim Talbot ’45, who at the time ran the only joint Soviet-American business venture in the world—Marine Resources, a seafood company.

As part of sister-school exchange activities, Lakeside and Moscow School No. 20 engaged in what was dubbed a “Telex swim meet” in 1984. During the event, swimmers raced at their own pools, and their swim times were telexed across the world between the two schools after each heat. The meet, which Lakeside won 53-21, was covered on both ends by NBC television. Goodwill was strong on both sides; Talbot commented that “this meet is the biggest thing since ping-pong diplomacy.”

A year later, Lakeside and Moscow School No. 20 engaged in a chess tournament of similar fashion. Each move was typed into a computer and sent halfway across the world. The six-hour tournament ended with four Soviet victories and a single draw; another game dragged on until 1 AM in Russian time and was continued afterwards by mail. Dan Ayrault, then Headmaster of Lakeside, quipped that “we are holding our own in swimming, but losing at chess.” After the meet, Lakeside congratulated School No. 20 for an “interesting and challenging match… now it is time for you to get some rest and us to practice.”

In 1986, ten Lakeside students, along with two teachers and then-Headmaster Ayrault, traveled to Moscow School No. 20 for five weeks as part of the first-ever lengthy high school exchange program between the United States and the Soviet Union. Nearly 100 students applied to go, very few of whom had knowledge about Russian society or language. Though all the students greatly enjoyed the trip, their impressions of Soviet Russia differed. One student said that “I expected a lot of gray… I didn’t expect all the colorful buildings.” Another reflected that “everyone said I wouldn’t like being in a Communist society because it would seem so restricted, but it wasn’t.” This diplomatic exchange garnered significant media attention: soon after the students returned to the U.S., the New York Times published an article titled “U.S. Students Gain Insights on Soviet Trip.”

Soon afterwards, Lakeside trustee Max Gurvich commissioned artist Parks Anderson to create a pair of identical sculptures for Lakeside and Moscow School No. 20. On October 14, 1988, the sculptures were unveiled in the courtyards of the sister schools in simultaneous ceremonies coordinated by telephone. Booth Gardner, then-Governor of Washington, spoke at the Lakeside ceremony. The modern-looking steel sculpture, about 22 feet tall, has two S-shaped wheels; Seattle Times art critic Regina Hackett described it as “something like abstracted Ferris wheels, and something like veils, machine-age cloths rising and falling in circular patterns.”

The sculpture made headlines for being the first art by an American to be publicly erected in Moscow—in fact, just half a mile away from the Kremlin, and right across from the Iranian embassy. Even after passing government regulation, installation was not easy on the Russian end. Further complicating things, Parks Anderson’s carefully-drawn assembly plans were not followed, and the sculpture failed to fit in its proper place. Anderson had to personally fly to Moscow, only to find that the Russian winter made it too cold to even pour concrete. Perhaps this is why the poles of the two sculptures show slight differences. The Lakeside pole has three sculpted heads at its top, while the Moscow one shows a bas-relief of scenes from the everyday lives of schoolchildren.

The Winds of Friendship still stands as a tribute to an amazing story of goodwill and exchange between two schools, and two countries. It is a touching reminder of our shared commitment to humanity and global mindsets. The next time you see this sculpture, pause and take a closer look—imagine its twin, standing in a different courtyard, spinning in a peaceful breeze five thousand miles away.