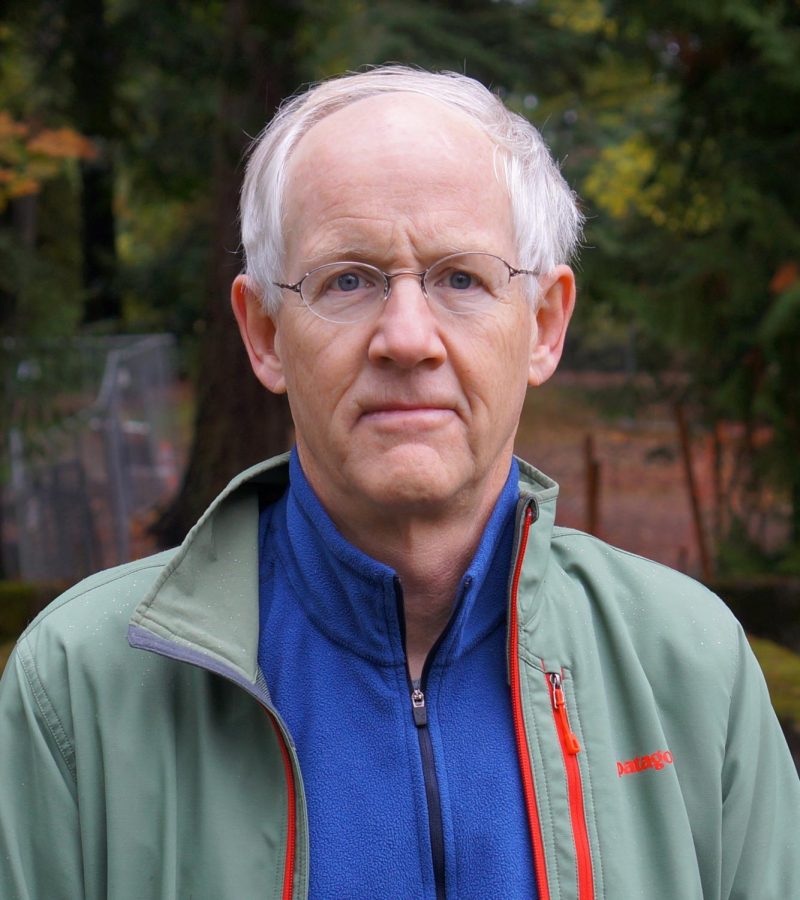

Tatler Guest Speaker: Blaine Harden

Prior to his talk on March 15, Mr. Blaine Harden, former correspondent for The New York Times and The Washington Post, asked Tatler staff to read his 2003 article “Montana Town’s Boys Are Its Last Gasp of Hope.”

“Montana Town’s Boys Are Its Last Gasp of Hope,” an article Blaine Harden wrote for The Washington Post, is, ostensibly, a story about a football game — the kind of article every newspaper in America carries nearly every day. But it’s really about demographic decline, ecology, and federal policy, Mr. Harden told the Tatler staff. “I rolled all of this into a sports story.”

Five days before the game, Mr. Harden arrived in the town of Geraldine, Mont. He and a photographer went around interviewing and photographing players, coaches, parents, townspeople, and local officials. They found that Geraldine was emptying out due to a federal subsidy that was paying farmers to grow native grasses rather than crops. So instead of retiring and giving land to a new generation of farmers, farmers were keeping vast areas of land into retirement, and with no new families coming in to farm, small towns like Geraldine were drying up. Between 1970 and 2003, the year Mr. Harden reported this story, the high school enrollment had dropped from 103 students to just 48.

And in the midst of this, football — six-man football — was a reason to get together. Mr. Harden interviewed a young field goal kicker who came to the town from Las Vegas because his mother had thrown a dart on a map and it had landed on Geraldine. As the thrilling game came down to a final play in overtime, it turned out that the young kicker scored the winning point, setting a state record in doing so.

Mr. Harden used his research to provide context to the energetic narrative of the game. “Using the pre-reporting I had done with the drama of the game — it gave the story a dramatic punch and gave it a human depth.” And that, to Mr. Harden, is what journalism can be.

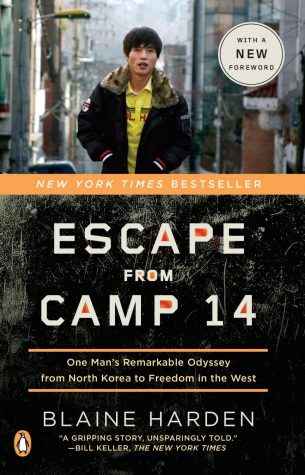

In his talk, Mr. Harden then moved into reporting through books. His 2012 book Escape from Camp 14 is an account of the first person born in a North Korean prison camp to escape to the West. Three years after the book was published, Mr. Harden learned that the subject of the book had fabricated some details about his life in the camp and his escape. Mr. Harden told the class that in reporting on a closed country like North Korea, which denies the very existence of the camps, it is impossible to independently verify some eyewitness claims and a journalist has an obligation to explain this to readers. If factual errors come to light, Mr. Harden said, it is important to acknowledge them immediately and correct them as honestly as possible.

In the follow-up reporting Mr. Harden did to understand what had happened and to correct the record, he learned that people who experience violent trauma as children often construct stories that blend fact and fabrication to help them survive. A psychologist who interviewed children of war told him that if he hears “a consistent, chronologically sound, intellectually coherent story from a survivor of terror,” Mr. Harden said, “he knows they’re lying, because, in his experience, those stories don’t exist.”

“If I had known about that when I wrote the book the first time,” he said. “I could’ve built that all in for the mendacity to be understood in context.”

Mr. Harden’s last example examined history and revision. In the 1800s, missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed by Cayuse Native Americans. They became martyrs, which was the story that Mr. Harden learned, growing up.

But Mr. Harden’s research revealed that Marcus Whitman had become a real estate developer, helping white families take ownership of Native tribal lands. And the Cayuse, who were dying of foreign diseases like measles, had a tradition of killing doctors who couldn’t cure diseases. Yet the martyr narrative became the history of the Northwest: it was in The New York Times, Encyclopedia Britannica, and textbooks from 1890-1910.

So Mr. Harden’s story — which grew into his latest book (“Murder at the Mission,” due out in April) — served as “an anatomy of a lie,” he said, “and how Americans are so susceptible to believing stories that confirm” their values and Manifest Destiny. At the center of the story was an area not far from where he grew up. “I didn’t understand the richness of this story until I started working on it,” he said.

The book ends with the Cayuse’s story, Mr. Harden said, “with their feeling that the arc of history has finally come back to them and told their story in a way that they think is accurate.”

As for journalism about large-scale topics, Mr. Harden feels that issues become relatable through telling stories. “If you can flesh out the humanness of a central character,” he said, “the development of a human being in all the richness of their humanity, you can tell people about environmental policy, urban policy,” and broader issues. “We’re all human beings, and we identify mostly with the suffering and triumphs of other human beings,” he said. And with this language of empathy, Mr. Harden advised Tatler to tell stories.

Technically, he notes that many great stories follow a similar arc, but “you never quite know what that arc is until you do the reporting.”

From A to Z, AZ's got it all. Especially existential boredom. Recently, Aaron cried while listening to Wagner's "Tannhäuser" on YouTube, the most he's...