“West Side Story” at 60: Showing Its Age, But Surprisingly Youthful

It is the season of romance, and coincidentally the season of ro-dance (I’m sorry), so I decided to take a dive into the classics with Shakespeare’s ever-prominent Romeo and Juliet.

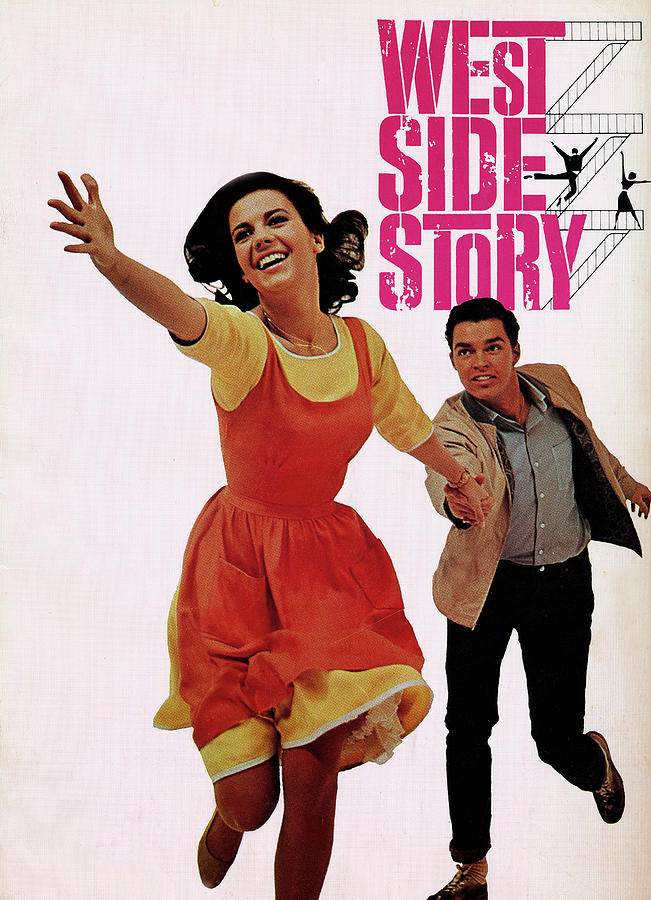

Sike, just kidding, I know the freshmen have enough to deal with without my ramblings on the history of the tragicomedy and the deliberate absurdity of two teenagers risking, then preventing, a civil war between two powerful families. Instead, I took a look at a film adaptation of the play, one widely considered one of the best: “West Side Story.” (Although, technically, “West Side Story” began as a stage musical, not a movie.)

I immediately went into “West Side Story” expecting little. Comparatively, of course. I heard the score was excellent (by the late, great Leonard Bernstein), and the choreography would be good, but beyond those two simple expectations I had little to go off of. So you could imagine my surprise when I actually really enjoyed the movie.

The music is of course great, but to an almost surprising degree. I don’t wish to go on a tangent, as Bernstein’s music could warrant a whole article by itself, but it was extremely intelligently made. They use simple leitmotifs for each of the factions, cuing them in and out as things happen relevant to their situation. For example, after the opening scuffle, the leitmotif for the Jets plays in the background as Officer Krupke arrives at the scene, musically implying his favoring the Jets over the Sharks (as he forces the Sharks to leave, and allows the Jets to stay).

Even more interestingly, almost all of the themes are variations of a three-tone leitmotif, a singular “hate” or “conflict” motif, which is rearranged throughout the movie to either represent the conflict, or resolution to the conflict. The fact that the Sharks do not get much of a conflict theme either also demonstrates the one-sidedness of the conflict between the two; the Sharks are just trying to live their life, while the Jets are thinking of the fight even in periods of calm.

The choreography is obviously excellent. The first scuffle is especially interesting—they manage to make ballet menacing—and demonstrates the high-octane energy of the whole movie—everybody moves like an acrobat, the leap and fly around. It is only near the end of the first fight when everything descends into chaos. Later fights are less organized, but each of the dance/song numbers are just as impressively coordinated. Of course, the songs going with those dances are all great—and the fact that they aren’t flawless is super charming, like they really are a bunch of unruly teenagers.

The actual plot is far superior to Shakespeare’s original play. Tony and Maria are actually likable, first of all, and much of their characterization is fixed in that they don’t marry each other literally a day after they meet (I mean, they make believe, but doesn’t count, okay?). They still plan to run away, but it is believable because of the passion they both have for each other. Both of them are very emotive, and I love how exaggerated they can be at times. Also, it helps that the age gap is (presumably) smaller.

Finally (and massive spoiler warning), I absolutely support the decision to have Maria live. In fact, I enjoy that they get rid of the whole “oh no, I gotta fake my death… oh no, she’s dead, guess Imma kill myself… oh no, now he’s dead, better stab myself in the heart” shebang, because (among the many narrative problems) it romanticises suicide. Tony dies from a gunshot wound from Chino, seeking revenge for Bernardo’s death, and Maria subsequently takes the gun and blames both gangs’ hate for the deaths. This scene is empowering, at least as empowering as a 1961 title can be, and far better than Maria taking a knife and sacrificing herself for someone else, because the “woman sacrificing herself for love” trope is so overdone that it is downright sexist at this point (ahem, the most recent “Mulan,” ahem).

Several of the undertones are surprisingly well-done, especially the racial conflicts. Of course there are many problems: there are several casual slurs that date the movie; sometimes the accents and mannerisms seem a bit too much; many of the Sharks are portrayed by a white actors in brownface; overall, a lot of the characters’ behaviors seem… extreme. The main conflict is ultimately a cross of teenage delinquency and xenophobia/racism, and is resolved by keeping with the traditional Romeo and Juliet message (both sides were to blame for the deaths), but beyond that the racial undertones are not directly addressed. Additionally, from a modern perspective, the outcome seems unfair; the Jets had the favor of a racist/xenophobic cop (some things never change), casually threw around slurs and sexist remarks, sexually harassed several women, and were overall just unruly. The Sharks’ only real fault was using the “they started it” argument. But keeping in mind that this movie was made in 1961, the fact that many of these themes were brought up at all is impressive.

Quite honestly, it’s amazing many of these things made it onto the silver screen in the first place: a tomboy/butch secondary character; an interracial couple (slightly stifled by the fact that Maria’s actress, Natalie Wood, is in fact Russian); largely positive representation of minorities; white privilege and systemic racism/xenophobia; etc. It even touches on the disappointments of the American Dream.

“West Side Story” approaches 60 this year. Despite some age showing through the gaps, it is definitely worth a watch.

You can take the woman out of the bird, but you can't take the bird out of the woman: meet Yoon Lee.