The Culture and History Behind Parasite

Korean President Park Geun-hye was impeached on December 9th, 2016. On March 10, 2017 a unanimous vote in court removed her from office.

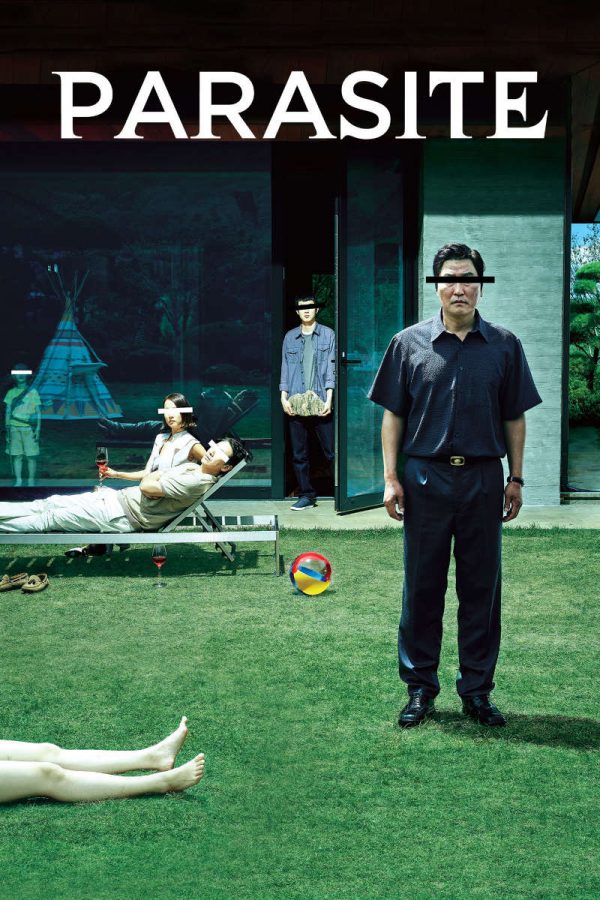

Parasite is a phenomenal movie. That much was obvious when it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. But even so, many were surprised when it actually won. Some were angry, many happy. Bong Joon-ho vowed to drink the night away. After all, a Korean film winning the Academy Award for Best Picture, widely considered one of, if not the, most prestigious title in film, was a pretty big deal.

Now, my parents are Korean immigrants, so I had some idea of the scope of this event, but beyond my impression of director Bong Joon-ho and what little I knew about the movie, I didn’t quite understand what made the movie so great. I mean, I won’t complain about a Korean movie winning an Oscar any time of the day, but 2019 was an amazing year for cinema. This past year we had films like Joker, 1917, Endgame, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Two of the three biggest Best Picture contenders, Joker and 1917, were some of my favorites of all time.

However, having recently watched Parasite myself, for the first time, I can say with confidence that it is unequivocally the greatest film of 2019. I love me a good war movie, and Joker was great, but Parasite just hits all of my “masterpiece” marks. Even Joker, with its amazing social commentary and Joaquin Phoenix’s phenomenal performance wasn’t enough to win it over Parasite for me. In every aspect Parasite was just a cut above the rest of the rabble.

Amazing direction, inspired camera work, great cast, genre flips, meta humor, a lingering sense of dread, as you realize that the fatal flaws in society highlighted in this movie are reaching a breaking point, a point at which that society either collapses in on itself or changes beyond what its original vision intended. You know. That kind of stuff. But there are already various reviews, essays, and videos regarding what makes this movie so good. Read those first. So I’m going to talk about what makes Parasite unique as a cultural and historical experience.

One major plot point in the movie is a suseok, or “Scholar’s Stone.” These are rocks and stones harvested by artists in East Asian countries like Japan, China, and of course, Korea. These stones are meant to emulate the natural beauty and irregularity of nature, stones left untouched by man and formed entirely by nature and erosion. This means methods like cutting, chipping, and polishing are not supposed to be used to create a suseok. As such, they range in size from boulders to smaller stones that scholars used to keep on their desks (hence the nickname). Collectible rocks should be dense, hard and hard to break, and rocks with a pattern or wave are more desirable, like the kind in Parasite. They are meant to be 3-dimensional, viewable at all angles like porcelain.

Although popular and artistic, suseok as an art form is below painting and calligraphy. High-tier art collectors may have one or two, but they would not be a center of attention. This represents further the social stratification of the Kims as they are the lowest of would-be art collectors.

(Spoilers below)

Now, in the movie, the stone represents good luck. When Min-Hyuk, Ki-woo’s friend, gifts the family a suseok fitted with a custom-made wooden base, he tells them it is meant to bring its recipients material wealth, and Ki-woo says “It’s so metaphorical!” as he places it on their drawer, the highest part of the house. And indeed it is, because after receiving it, things start turning around for the family. The family doesn’t have cell service, live off of free cafe wifi, barely have enough for food, and scrape a living by folding pizza boxes. And one after another, the whole family lands jobs with the wealthy Park family– cleaning and cooking, driving, and tutoring the children.

But the suseok comes back when the family’s luck starts to run out. In a massive storm, their basement apartment floods, and one of the few items to be salvaged was the suseok— floating up through the septic water (suseok are meant to be dense so it should have sunk, but it is possible that it was just retrieved from a high up place). Ki-woo takes it to the Park family house, intending to kill an unfortunate couple living in the Parks’ house’s secret basement, who were blackmailing the Kims. Then he literally drops it down a flight of stairs. Now without its wooden base, covered in sewage water, being used as a murder weapon, dropped down a flight of stairs, and soon to be covered in blood, the stone takes its karmic revenge when the man hidden in the Parks’ bunker uses it to bludgeon Ki-woo to near-death (see: Chekhov’s Gun). And thus, the family plunges back into poverty.

The suseok is the perfect opportunity for the Kims to enterprise into the sophisticated world of the Parks. But alas, in this film it is only an invitation of violence.

(Spoiler safe)

There are many, many other examples of Korean culture and language making this film unique. However, I do want to talk about the history and background that brought this film to light.

In 2014, the MV Sewol sank nearly a mile offshore from Donggeocha Island. 304 people died, of them almost 250 were high school students. The reaction to the disaster was, well, disastrous. The coast guard was slow to react and even slower to take proper action. Initial reports led parents to believe all 328 passengers were rescued. The captain was gone. The president was missing for several hours, supposedly to get a botox injection and to consult a fringe religious group leader, later to be found guilty of corruption when the extent of her ties to the government was found. Over the next few months the death toll rose from dozens to hundreds. Much of the crew was charged with counts of negligence, homicide, and violation of maritime law. A nationwide manhunt was put forth for the arrest of the man in charge of the company that operated the Sewol, later to be found dead in a field. Pope Francis visited. The US Marine Corps lended their help. The government tried to downplay the size of the event until word went out over the course of months. Over the next few years, the wreck was salvaged and bodies recovered, some yet to be identified. And one thing nearly every person in the country could acknowledge was that President Park Geun-hye’s disaster response was horrid, disrespectful, and in many ways ignorant.

Beginning in 2016 candlelight protests began. Citizens taking to the streets, holding and waving candles in the darkness in protest of President Park Geun-hye’s disastrous response, compounded with years of corruption beforehand. The movements culminated in late 2016 to early 2017, with millions of people at times all peacefully protesting against the Park Geun-hye presidency, ending with her removal from office in 2017 and sentencing to 25 years in 2018 after being found guilty of abuse of power and coercion.

Many claimed it to be a revolution. To some, a return to normalcy. To some, an insurgency. One thing that became clear was that years of corruption were being rolled back, rabbit holes being filled, and the once-shady government response around freedom of speech finally being discovered.

As the handover of the presidency to Moon Jae-in began, documents revealed that she and others had created a secret blacklist of thousands of left-leaning artists, producers and entire companies who had won her disfavor. This ranged from actors who had portrayed her in SNL skits to directors that made movies criticising the government, to producers, to distributors to entire companies that were brought down. One of them was Bong Joon-ho.

Now, Bong was rather lucky since he had already been established as a great artist and an impeccable director. He already had films like The Host and Snowpiercer under his belt. There were multiple reasons for his blacklisting, but among them was his striking socio-political criticisms, including in The Host and Snowpiercer. And frankly, that’s part of Bong Joon-ho’s trademark — scathing social commentaries.

Bong Joon-ho entered his freshman year at Yonsei University in 1988. The year before, in his senior year of high school, nation-wide protests were underway for the ousting of the military dictatorship of President Chun Doo-hwan. Protests flared up in mid-June of 1987, in response to the torture and death of Park Jong-chol and the death of Lee Han-yeol to a tear-gas grenade to the head. Both were college students. By July the regime had acquiesced to the people’s demands. If you can’t tell already, Koreans are really good at impeaching unfair administrations.

So by the time 19-year old Bong Joon-ho entered one of the most prestigious colleges in the country, the melting pot of the student revolution, pursuing a degree in sociology. If you were a Korean student in 1988 pursuing a sociology degree, it was quite impossible to not think about inequality. He already had to think about it because of current events, but compounding it with his degree and attendance to Yonsei added to his inspiration.

While attending college Bong founded the Yellow Door film club, which is still a popular club at Yonsei, and made cartoons for the Yonsei Chunchu, the school newspaper. One of his most famous strips was a commentary of how privileged, even ignorant, college students were:

(*insert strip*)

Back then, college students, during their free time, could call for fast food and have it delivered to them. Many fast food workers back then were the same age as those students, but they had to work to support their family while the students partied and played during the festival times. In this strip, the fast food worker knows his future is not bright.

I visited Yonsei University some time ago. Although the school looks far different from what it was in the 80s, it is not difficult to imagine the young men and women lying in the sun, laughing, and having a picnic, as minimum-wage food workers deliver to-go Korean comfort food right to them. Imagine being this person, making barely minimum wage, watching these bright young folks your age or younger going to this prestigious school and having fun, not caring about the 20-something-year-old delivering their food. So, in response, Bong says what amounts to, “While it is festival season, let’s look around sometimes” as the fast food worker delivers food not to the students, but a janitor who must clean up after these careless kids. Two low-class people serving a high-class school. These themes of the ignorant high class, feeling like they have to look out for the lower class but don’t, are themes that permeate Bong Joon-ho’s works, refined into the commentaries of Parasite. These themes are also what got him blacklisted.

Parasite and its universal success represents the entrance, perhaps return, of Korea to the world of freedom of speech and high filmmaking.

(Spoilers from here to the end)

One last thing. Who is the parasite, in Parasite? The obvious answer is the poor family, the Kims. One after another they get every person in service of the Park family fired and replace them with one of their own. They steal their food, they arguably steal money, and when the Parks leave for a camping trip, the Kims use their water, eat their food, and drink their alcohol. Another candidate would be the man in the Parks’ basement, who was literally a parasite in the definition of the word: an organism that lives in or on an organism of another species (its host, in this case the wealthy Parks) and benefits by deriving nutrients at the other’s expense. Perhaps it is the father, Kim Ki-taek, at the end of the film when he goes into hiding. But rather, I feel like everybody in this movie is a parasite in some way. The first two are obvious red herrings, but they are still parasites. The Parks are less obviously parasites, but they nevertheless are. They cannot cook, cannot drive, cannot clean, cannot handle their children, cannot even throw a party without the help of someone else. And despite this, they complain about the way the poor smell, how they are “dirty,” and they take money from their servants’ pay. And yet they make cruel sexual fantasies of being “poor” and “dirty,” even as thousands sleep in a gymnasium because of a flood they think is just a minor inconvenience. They parasitize off of the poor and society in general.

In Parasite, everybody is a parasite.

Here’s a list of good sources about the topics I talked about:

Suseok meaning:

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/guide-suseok-stone-parasite-1768059

June 1987 struggle:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/June_Struggle

2016-17 Candlelight protests: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016%E2%80%9317_South_Korean_protests

Impeachment in Korea: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/10/impeachment-president-south-korea-us-donald-trump-park-geun-hye/

CJ Vice Chairwoman (distributor of Parasite and Snowpiercer): http://m.ajudaily.com/view/20200211105616893

Bong Joon-ho blacklist: https://www.insider.com/parasite-director-bong-joon-ho-blacklisted-south-korea-2020-2

Korean blacklist: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/12/world/asia/south-korea-president-park-blacklist-artists.html

Yonsei Chunchu (comic strip): https://m.blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=yanink&logNo=221806246614&proxyReferer=https:%2F%2Fm.search.daum.net

Bong Joon-ho comic strip (bottommost strip): https://mblogthumb-phinf.pstatic.net/MjAyMDAyMTJfMTQ4/MDAxNTgxNDk0MzQ2ODkw.

You can take the woman out of the bird, but you can't take the bird out of the woman: meet Yoon Lee.