Over the past few years, Tatler has covered a wide range of administrative, academic, disciplinary, and fiscal decisions that Lakeside has made. Whether controversial or highly supported, what remains the same between all decisions are the groups of alumni, administrators, faculty, and members of the community who play a part in making them.

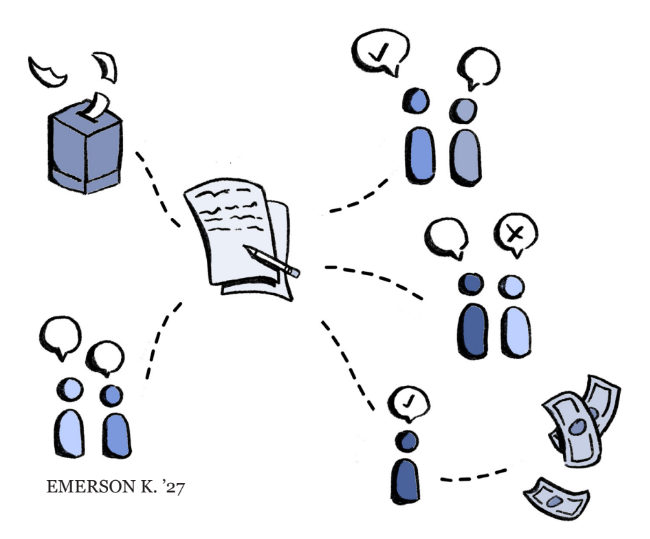

Students have two main ways of participating in the decision making process: a direct method and an indirect method. They can suggest ideas directly to a faculty member or administrator, or they can propose an idea to the Student Government through a suggestions box located in Bliss Hall. That idea is then advanced as a potential Student Government project. Each project begins with a proposal, written by a representative or a group of them, that details who will be involved in making that idea a reality, the process of how that will occur, and necessary support or funding that project might require.

Once a student representative or group of representatives draft a project proposal, it is sometimes subject to the review of the senior President and Vice President. The proposal is finally reviewed by chemistry faculty and Student Government advisor Dr. Jon Russell and Upper School Assistant Director Jeff Bonar. If they and any other relevant administrators approve, then the representatives who proposed those ideas are responsible for executing the project and monitoring its effectiveness.

Student Government in recent years has received widespread criticism for its ineffectiveness and lack of transparency with the student body; in particular, many Lakesiders assumed that group of twelve students was largely responsible for the “Invisible Device Policy” instituted by the administration earlier this school year. Raymond Z. ’27, who currently serves on Student Government, describes the body as one with “no ability to make real change.” He contrasted it with Student Government in the ’90s, when the body initiated discussions with the administration in response to student protests over the suspension of eleven seniors for hazing. Those talks ultimately led to the formation of a Student Court, which later became the Judicial Committee.

Until this year, the entirety of Student Government determined each club’s annual budget on a case-by-case basis. Today, only a small subset of representatives, and often only the Student Government Treasurer, have near-unilateral control over club funding. The administration provides funding for all competition, registration, and travel expenses, which typically include the school’s debate and Model United Nations clubs, along with its robotics team. As for all other club expenses, they are directly taken from club accounts. The amount of individuals determining club budgets was decreased in response after confusion about how club funding “worked,” according to Raymond.

The diminishing of decisions unrelated to events that Student Government makes as a group contributes to an atmosphere that, in Raymond’s words, makes Student Government “essentially [an] event-running committee”, as opposed to the body’s ideal role in making “substantial change in the community.” He adds that “We [Student Government] definitely don’t make important decisions, largely because we don’t have agency to make important decisions.” He adds that in conversations with fellow representative Timothy D. ’27, there exists a sentiment that “StudGov is ideally a proxy from the students to the administration, while it is currently a proxy from the administration to the students.”

Students in the past have called for stricter regulations on how much homework is assigned to students and when, referencing weeks where they are bogged down with assignments and others where they have virtually none to complete. Student Government candidates in the past have campaigned for systems similar to that of the Middle School, where teachers coordinate with each other to balance student workloads and ensure that no single week has a particularly large or small amount of exams and large projects. As for the reason the Upper School has yet to have an overarching solution, Academic Director Hans de Grys explained that it is incredibly challenging to coordinate amongst all those classes. Elaborating on that point, he believes that “everyone agrees that trying to smooth out student workload is a good idea;” however even as a ninth grader, which is the grade when the most students are taking the same classes, there still is so much variety in the courses students choose.

Instead of the organization-wide approach the Middle School takes, Mr. de Grys explains that he recommends students to talk to their teachers about any issues with workloads. He uses his own class as an example, where he checks in with students about planned assessments and adjusts when needed. In his view, even a well intended calendar that limits tests to certain days would create its own problems. A class might reach a natural stopping point, typically the end of a unit, yet students’ busy calendars could force delays in when a test is taken. Students would then face a test on material learned weeks earlier. He also noted that whenever he tries to move an assessment, opinions among his students usually split in every direction. One group wants the earlier date, another wants the later one, and a third group does not care either way. Mr. de Grys sees this phenomenon, which undoubtedly would occur outside of the single class he teaches, as proof why a single “Middle School-esque” rule cannot meet the needs of every student.

Beyond the workload question, Mr de Grys outlined how broader academic conversations are conducted. On paper, the academic decision-making process starts at the top with the school mission and with a strategic plan that the school revisits every five to seven years. The head of school, the Upper and Middle School directors, the academic dean, assistant directors, college counseling, and experiential education all take part in those conversations. They invite input from students, alumni, and the Board of Trustees. Those meetings tend to focus on broad questions. What does the school want students to learn? Where does Lakeside need to change direction? What new pressures or issues has the community raised?

From there, decisions are made on a far more granular level. Disciplinary decisions are delegated to bodies including the Judicial Committee, and social or campus life decisions are often delegated to Student Government. As for curricular decisions, they are delegated to the Curriculum Committee, which meets in the fall and is composed of the department heads, other faculty members, administrators, and four students: two juniors and two seniors. Each year, teachers, departments, and students submit proposals for new classes and major changes to existing ones. This year, there are around fifteen proposals for the committee to review, both for summer offerings and ones during the school year. Notably, one proposal is aimed at reformatting the current English curriculum for juniors.

According to Mr. de Grys, each proposal goes through several stages. First, an individual department or teacher writes up an idea as a proposal, typically after at least a year thinking through it and discussing the idea with him and Upper School Director Ryan Boccuzzi. The Curriculum Committee then reads the proposal, discusses it in a meeting, and asks questions. Members debate where the class sits in the larger program, what students it serves, whether there is enough staffing, and which existing course hours it might displace. At the end, the committee votes to approve the course, reject it, or send it back for revision.

Although teacher votes significantly outnumber student votes on the committee, that is not to say that they serve a marginal role. In the spring, the student representatives on the committee prepare a report on academics at Lakeside from a student’s point of view, often conducting surveys and interviews that focus on a wide range of subjects, from assessments and homework to equity between classes and the core curriculum.

Below the committee, and outside of its jurisdiction, academic decisions are largely left to individual departments and faculty. For example, the Science Department’s restructuring of the physics curriculum this year and the History Department’s decision to adjust the H100 through H300 sequence are both examples of decisions largely taken by department heads as opposed to an overarching body. Departments talk with Mr. de Grys and Mr. Boccuzzi before they make any large shifts in what or how they teach, but the administration does not initiate those conversations or decisions.

Some changes skip the Curriculum Committee entirely and move through administrative channels. The sexual violence prevention program came from a broader recognition that students needed explicit education in that area. That program created a required course rather than an elective, and it came out of discussions among school leaders and community voices, before moving into the class schedule for Lakesiders.

Seen together, these layers form a rough map of how Lakeside makes choices on all levels of organizations, and how those decisions that affect and sometimes define Lakesiders are made. The strategic plan and mission set the direction and motivation for all decisions. The Curriculum Committee handles new course proposals and curricular changes that affect many students at once. Departments control the fine details of how they teach their disciplines. Student Government, despite its limits, remains one route for student concerns to reach administrators. Individual conversations between students and teachers fill in the more granular decisions, especially on day to day issues like tests and homework.

While this structure involves students in at least some formal decisions, students often witness only the results of the process and not the debates leading to them. In regards to that, Mr. de Grys has some short and blunt advice for students wishing to make a change: Don’t complain. They can speak directly with him, with department heads, or with their advisors. They can also enter more formal channels, including applying to the Curriculum Committee, which Mr. de Grys said might open spots to underclassmen representatives, and using Student Government as an avenue for delivering policies to the ears of the administration.