Six students looking forward to the annual Student Diversity Leadership Conference (SDLC) in December of 2024 were met with an unwelcome surprise: due the popularity of the conference, spots were doled out using a lottery system, and Lakeside was not selected this year.

What happened instead was Lakeside’s first ever weeklong student trip touring the South. In late February, Efe E. ’25, Rahamatou M. ’25, Cailyn C. ’26, Chloe M. ’26, Makalika P. ’27, and Owen S. ’27, led by teachers Debbie Bensadon, Bryan Smith, and Latasia Lanier, visited centerpieces in the battle for Civil Rights like the Edmund Pettus Bridge (Selma) and 16th Street Baptist Church (Birmingham).

Day one, after a long day (with the time zone difference) flying Alaska Airlines, students landed around 4:30 p.m. in Atlanta where their trip leaders rented two spacious SUVs — one dubbed the Smithmobile (driven by Mr. Smith) and another called the Yappertron (driven by Ms. Lanier) due to the strange phenomenon where every time, passengers in Mr. Smith’s vehicle would be dead asleep and, conversely, students chatted wildly in Ms. Lanier’s car. Each student getting their own row of seats in the Smithmobile, Chloe suggests, may have been a factor.

Driving ahead, 152 miles later, they arrived at a Hilton in Montgomery, Alabama for the night. Dinner was Bojangles, Southern fast food — the first of their many unique culinary adventures.

Day two, the adventure really began. Students were instructed to meet in the lobby at 8:30 a.m. However, Chloe notes, the no-device restriction on the trip, although increasing group connection overall, made it difficult for students to wake up on time. In particular, Owen and Efe, who roomed together, seemed to consistently struggle with this rule. The first morning specifically, Owen recalls, Mr. Smith “was banging on the door and we had a heart attack.” At least Cailyn, not taking phone alarms for granted, remembered to bring an alarm clock.

After some complimentary breakfast at the hotel, the nine travelers strolled to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a blocky building. Then the group headed to their first (and Chloe’s favorite) museum — the Civil Rights Memorial Center.

“It was really cool because the memorial [center] powerfully communicated the evolution of racial oppression from slavery to also mass incarceration, and [put] a lot of emphasis on how discrimination [still] continues today, especially in the criminal justice system,” Chloe remarks.

At the museum, Owen explains, students were given hours to wander the sites at their own pace and reflect on their emotions or connections to lessons at school. “A lot of the time we would kind of exceed that expectation,” points out Owen. “Just because we were really enjoying the area and really trying to take it all in.”

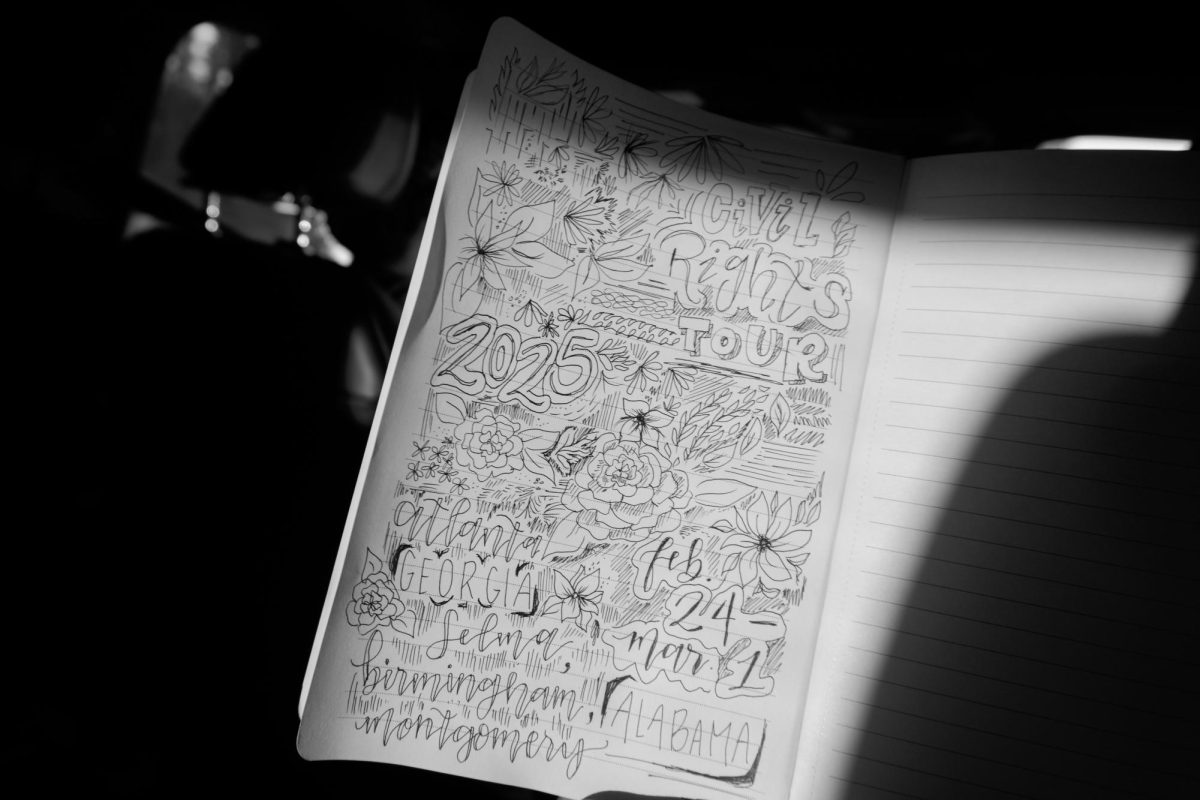

Usually, the reflection came in the form of journaling. Technically, it wasn’t required, but rather advised. In fact, the trip leaders also would quietly step through the halls and take notes of their own.

“The first day we were provided with a journal prompt and given around 45 minutes to just write stuff down. At first I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a lot of time.’ But when you start writing, you just get [into] a flow state,” remembers Owen.

Chloe remembers roaming down a warmly-lit ramp gazing at huge, bronze-colored steel blocks hanging from the ceiling. The 805 stone fixtures — each the size of a human — had county names engraved on their bottoms, each place once the site of a racial terror lynching. Names covered the sides of the blocks, marking individual victims.

After leaving the museum, the group drove to Selma, where they grabbed a bite at Lannie’s Bar-B-Q Spot. They then set out for one of the most memorable experiences of the trip.

As the midday sun shone over the city, the nine travelers drove to pick up their tour guide — an elderly man named Kirk Carrington who had participated in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches (including the historic day known as “Bloody Sunday,” when law enforcement brutally assaulted peaceful protestors) ”) at age 14.

Owen remembers a memory Mr. Carrington shared: “Teachers would turn around towards the board with their backs facing the classroom so students could pop out the windows to go join some of the marches that were taking place [since] the teachers weren’t allowed to promote them. Deep down, they wanted them to, so they literally turned a blind eye to it.”

Chloe adds how “personal and real” Mr. Carrington’s stories of singing songs while walking the 50 miles to Montgomery were, highlighting the importance and power of student activism, as well as stressing how nonviolence gave protestors “the sense of moral authority [that] separated them from the oppressors.“

Owen eventually found himself conversing one-on-one with Mr. Carrington.

He was telling me he saw himself in me,” Owen recalls. “[Mr. Carrington] gave me a shirt: the Selma Foot Soldiers was the group that he was a part of who participated in the marches.” Owen describes him in hindsight as a “familial figure” — an uncle or a grandpa. In fact, his one regret of the trip? Not chatting more with him.

After touring the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Mr. Carrington stated he “wanted to show the group something.” What students saw next gave them a kick in the gut.

Greeting them were fluttering red flags with diagonal blue stripes dotting a graveyard, and 40-foot statues of figureheads who had slaughtered Black soldiers — a Confederate war cemetery.

“[It] was pretty crazy seeing how people still so openly disagree with everything about me and what I stand for,” Owen reads from his journal. “A lot of these plaques by the statues made me see just how blinded by fear, hatred, and prejudice people are; they often stated that the people were fighting to protect some thing that was morally correct.”

The cemetery land, Chloe remembers from Mr. Carrington’s explanation, was bought by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to “remind the majority-Black neighborhood around the cemetery of ‘their place.’” Because it was private property, the community could do nothing but watch.

“[It] really just opened my eyes to how a lot of these issues still are present in the world today and not as insignificant as I may have thought,” Owen says.

Day three was six hours at the expansive buildings that comprised the Equal Justice Initiative Legacy Sites in Montgomery — one of Rahamatou’s favorite memorials.

Reflecting on what she saw, she describes it as being “sucked into the horrible reality of slavery when sculptures of ancestors are chained by unimaginable, inhumane contraptions. Arms are bound in awkward positions, mouths are shut by muzzles.”

Owen explains feeling “powerless and angry” reading the names at the lynching memorial, seeing “how people would get killed over simply walking in the wrong spot” and “small actions could lead to such swift and violent responses.” Day four consisted of visits to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, 16th Street Baptist Church, and Kelly Ingram Park.

Across the street from the church where four young girls were killed in a racially-motivated bombing was a park that commemorated the bombing and broadly, peaceful protesting in the Civil Rights Movement.

In the park was a statue of the four girls — depicted as “a product of a vision from one of the girl’s sisters who said that she had had this vision of exactly that scene after the bombing,“ remembers Chloe.

For her, the church was incredibly impactful, so much so that she decided to write her 8-page junior history paper on the bombing. The trip “reshaped my understanding of racism not as a past issue, but rather a persistent, evolving challenge. It made me realize that laws can change, but attitudes have to change too.”

Rahamatou also distinctly remembers strolling through the park and seeing “statues in motion,” which she explains as sculptures working in tandem with other sculptures to tell a story. One such statue was of people retreating from fire hoses used by police officers shaped like guns — all part of the commemoration of nonviolent demonstrations.

One specific photo she took that stuck with her was of Efe and Owen, sitting behind sculpted bars. “You’re able to imagine yourself in that type of situation. You’re not necessarily just hearing from a teacher that’s giving you a lecture, [but] really immers[ing] you[rself],” Rahamatou says. She explains feeling a sense of openness and receptiveness to emotions the entire trip, and on her journey through the park?, she felt those emotions come and go.

After a heavy day of content, dinner was the meal that made Rahamatou’s day: Urban Hai, an Asian fusion. There, she had the best dish of her trip, feasting on Korean barbecued duck breast with a side of bao buns and greens.

Day five was the group’s final full day in the South. Their entire day was spent in Atlanta visiting Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. preached, as well as the King Center — a sprawling complex surrounded with greenery focused on Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy.

At the end of the walk through all exhibits, Chloe found her most memorable quote of the trip, from Dr. King: “Anyone can have greatness, not fame, but greatness.”

Since it was the last day, she went to sit down on a bench for her final reflection. The sun was shining. Kids were running across the park. Surrounded by flowers and facing a fountain with Martin Luther King Jr.’s crypt, she had one to two hours to tackle the last topic of discussion for students: What can they bring back to Lakeside?

Before the group departed, they spent their final night at the hotel snacking on pizza — Owen managed to snag an entire pepperoni, sausage, and beef pizza for himself — and watching Selma, a historical film based on the Selma to Montgomery marches.

When the sun rose Saturday morning, everyone promptly packed their bags for Hartsfield-Jackson. With one last good look at Atlanta, their Delta flight took off at 3:15 pm, concluding their trip. Aside from their suitcases and backpacks, students also carried with them thoughts for improving Lakeside.

On May 22, students presented to the Board of Trustees, who are considering similar future trips. Chloe remarks that the Board “seemed impressed with the students’ depth of knowledge from the trip and were definitely curious.” One big takeaway only experiential education could bring: the importance of visiting landmarks in person.

“You go through U.S. history and hear about traumatic stories, and you’re like, ‘okay, that’s really bad,’” explains Rahamatou. “But then once you visit these sites, you truly begin to understand the horrors of what happened, but also the triumphs that a lot of the leaders [of] the Civil Rights movement w[ere] able to realize.” Owen emphasizes that point, valuing how the trip helped provide an “unfiltered look at some of the things that are still plaguing our country.” That bluntness helped him understand to speak up for injustices. “That’s my personal role and what I’ve learned to teach others on the trip,” he adds.

Similar to many other students, Owen found the most valuable takeaway wasn’t “the statistics portion of it but instead the emotional portion of [the trip]. Especially being able to go on the walking tour with someone who literally was a part of [the Civil Rights movement] really achieved my goal right then and there.”

Chloe remarks that the car rides were a great bonding experience, considering carpool groups would be constantly shuffled to mix students together. “Everyone had their own thing to contribute to the group,” Rahamatou adds. All in all, the group ended up growing tightly knit, even the teachers.

All the success of the trip can in part be attributed to the weeks of pre-trip planning. Mr. Smith led three pre-tip sessions in the Fireplace Room in which he explained cultural differences and important context from his time living in the South. In addition, students went on a walking tour of Seattle’s Central District in late January.

Trip leaders also carefully planned out everything from the order of site visits to the restaurants students dined in. Ms. Lanier explains the goal was to begin with heavier visits like the lynching memorials and have the tour conclude in Atlanta “on a note of hope and excellence” with sites commemorating Dr. King’s legacy and exploring modern activism. Profe Bensadon emphasizes the forethought of the site orders, discussing how her experience visiting Holocaust museums and concentration camps as a Jewish person underscored the importance of considering the lasting emotional impact of the trip.

The final aspect of the trip that required much thought? The students.

“I thought it was a fantastic group,” Ms. Lanier explains. “All of them are leaders in their own realms, so when they were going through these experiences, it was not only always personal.” All in all, she hypothesizes that intent to bring something back to the community made the group “far more engaged [than] other groups would have been.”

As for the origin of the trip, Profe Bensadon notes “the idea came to me when I realized that we were not gonna go to SDLC.” But with her adamance to have at least some experience for students, she followed up with Nancy Rawles, a history teacher who had gone on a similar trip in the South.

In fact, a trip similar to these occurred a few years ago with Upper School teachers like Stephanie Wright, former head of the history department, and Zinda Foster, former service learning coordinator, as a “recon trip” to see if they could integrate a similar trip into the class curriculum. However, funding limited Lakeside’s opportunity to host similar trips the following years.

Other schools around the nation have hosted similar trips in the South. For example, Profe Bensadon recalls that locally, University Prep sends their seventh grade class annually. In addition, the Brearley School in New York has a Civil Rights trip for their whole junior class in tandem with the history curriculum.

Looking to the future, Profe Bensadon is optimistic about new social justice trips. For example, trips exploring migrant or indigenous communities in California. She encourages interested students to apply for future trips.

All in all, with the framework set up by previous explorers, when SDLC was scrapped, the money, ideas, and people came together to orchestrate a six-day journey that would provide lessons for a lifetime.

Lakeside’s Inaugural Civil Rights Trip Brings Emotional Epiphanies and Camaraderie

Timothy D. ’27, News Editor

Jun 4, 2025

About the Contributor

Timothy D. ’27, News Editor

COMMON NAME: Tim/Timothy/Timmy

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Timothy Dong

TYPE: Extrovert

PERSONALITY: Energetic, Charismatic, Imaginative

DIET: Anything goes, loves Turkish pastries

AVERAGE ATTENTION SPAN: ~5 minutes

HABITAT: Can be found all around the school talking with friends or working on homework, most common in the library wasting time

HOBBIES: Plays modded Minecraft in free time, or goes hiking out in the Cascades