“Three, two, one, zero… FIRE!” The words echoed across the wooded corner of what is now the soccer field. The roar came first. Then the crackling, explosive power — and stench — of propellant. Smoke poured out of the makeshift bunker, and cheers erupted from a group of students huddled inside, their excitement spilling over the radio channel. “It didn’t blow up! It didn’t blow up!” Randy Kay, age 18 at the time, yelled triumphantly, his voice crackling over the intercom. The students would later find that their rocket also accomplished another not-so-remarkable feat: alarming nearby residents enough to dispatch both the Seattle Police and Fire Departments to Lakeside.

This whole story begins on October 4, 1957, as the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite circled the globe. Brent Logan ’59 and a small group of Lakeside students had an idea: to create a club where students could explore rocketry firsthand. The idea’s sponsor? Logan and a group of like-minded students captivated by the dawn of the Space Age. The idea’s name? The Lakeside Rocket Society.

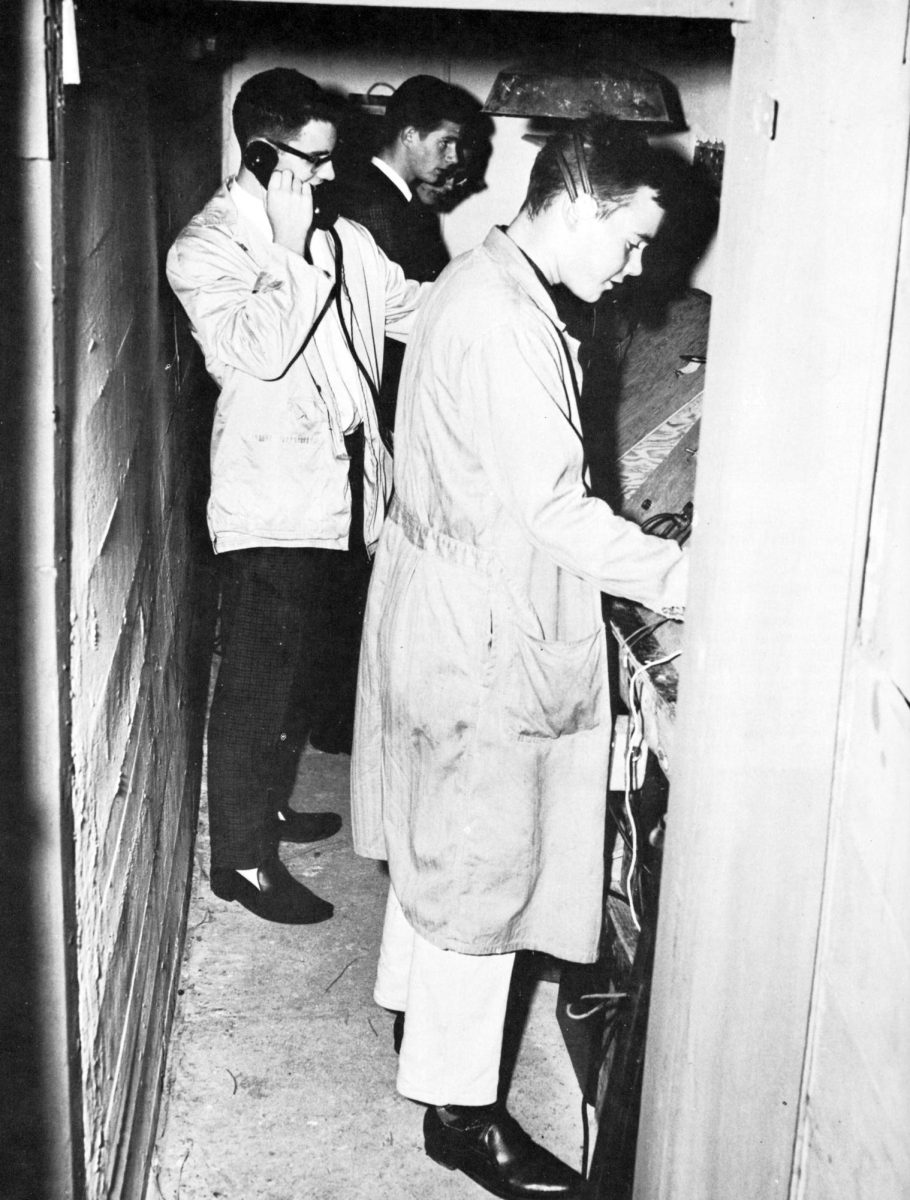

Their goals were bold: not only to build and launch rockets but to design their own solid-propellant motors and test them right on campus. In those first few months, the Society set up shop near Parsons Field, where their makeshift testing ground consisted of a concrete bunker and salvaged control panels. There were no blueprints, no tutorials — only borrowed textbooks and their determination to figure things out. It didn’t always go smoothly. One of their early engines exploded spectacularly during a test, prompting neighbors to call the police. “It was loud,” Logan later recalled. “But we saw it as a success. We learned what not to do.”

By the following year, the LRS was firing on all cylinders — quite literally. Under Logan’s leadership, the group expanded its scope and expertise, and Lakeside students, once again, leveraged their willingness to learn to build engines capable of producing jaw-dropping amounts of thrust. Their first major breakthrough came in 1959, when the XLR-2b engine shattered a national amateur rocketry record, generating between 800 and 1,000 pounds of thrust. News of the achievement spread beyond the Lakeside campus, earning the society recognition as one of the most advanced high school rocketry programs in the country.

But these weren’t just experiments; they were events. Test firings became campus spectacles, attracting students, faculty, and even local reporters. Each launch was a chance to celebrate science and teamwork — and, occasionally, to troubleshoot. One particularly ambitious test in 1961 saw the rocket sputter and fail to ignite, prompting one member to quip, “Well, we got the smoke part right.”

During its golden era (1962-63), the LRS expanded its operations. They transitioned to using ammonium perchlorate composite propellants, a cutting-edge material typically reserved for professionals. The group also began working on multi-stage rockets, envisioning more sophisticated launches than ever before. For a while, it seemed like the sky truly was the limit.

By 1964, however, the society began to face challenges. With the departure of founding members like Brent Logan, leadership passed to a new generation. While these students were no less passionate, the increasingly technical nature of the projects created a rift between older members and underclassmen. “We were building things so complex,” one former member later admitted, “that it was hard to bring younger students in without overwhelming them.” The society tried to bridge this gap by hosting lectures and inviting younger students to observe experiments, but participation suffered.

Despite these internal struggles, the LRS continued to push boundaries. In 1964, they successfully tested the XLR-201, an engine fueled by advanced composite propellants. The test firing, delayed for hours by technical glitches and rain, was a testament to the group’s persistence. As the engine roared to life, the team burst into cheers. By 1965, the society was nearing the end of its journey. Interest waned as members graduated, and the proving ground near Parsons Field fell into disrepair. The group’s final years were marked by dwindling resources and participation, though their passion for rocketry never wavered. One of their last projects, a multi-stage rocket capable of reaching unprecedented altitudes, remains unfinished. When the school repurposed their test site for athletic facilities in 1966, the Lakeside Rocket Society officially disbanded. It was the end of an era, but the legacy of the LRS was far from over.

Many of its members went on to careers in science, engineering, and aerospace, crediting the society with sparking their lifelong love of innovation. For Lakeside itself, the society’s story became a symbol of what students could achieve with curiosity and determination. In later decades, new extracurricular programs — from robotics to coding — carried on the same spirit of exploration the Rocket Society had embodied.

Today, the echoes of those early test firings may be long gone, but the lessons they taught remain resounding at Lakeside in the minds of students every day: dream big. Work hard. And don’t be afraid of a little smoke and noise along the way. Perhaps one day, the sharp crackle of ignition and the thunderous roar of a rocket motor will echo once more across the track where the old bunker once stood — accompanied by the jubilant cheers of students and exasperated groans from just across the street.