In 1936, a notice titled “School costume chosen” appeared in the Tatler, advertising “attractive new outfits” for the “well-dressed Lakeside boy.” These outfits consisted of a maroon blazer and gray flannel slacks, with the selection of shirt and tie left to the individual student. Seniors were to wear suit coats. At the time, most prohibited were “dirty cords” (corduroy slacks that were never washed, to maintain a nice stained and brown color) and sweatshirts, with Tatler declaring them “taboo”.

The dress code continued through the 1930s and 40s, though restrictions did loosen up. In 1939, Tatler reported on a petition allowing students to wear sports shirts in place of neckties and collars. The war against sweatshirts and sweaters was still on, however, with headmaster Robert Simeon Adams admonishing disobedient students flaunting the forbidden clothing items. “‘Sport shirt,’ defined, does not mean ‘anything,’” Tatler wrote, “but refers to shirts with open collars or regular shirts without ties. If these simple regulations are not observed, and blazers, suit coats, or letter sweaters are not worn by the respective classes, this privilege will be taken away.” Little did students know that in five years, the very Mr. Adams would suddenly authorize the wearing of sweaters and sweatshirts, much to the joy of the student body.

In the in-between period, Lakesiders continued to express their sense of style in bizarre and unorthodox ways. In 1942, Tatler published a scathing critique of Lakeside’s fashion sensibilities: “Darwin said that man sprang from the monkey,” they wrote. “Judging by the current fashion trends at Lakeside, however, we would call it only a demoralized crawl.” Though Tatler enjoyed attacking school trends, it was not beyond targeting individual students and their unique fashion flair. Some of the items they assailed included…

- Bow ties. In particular, “Walt Lewis’ yellow one-footer” and the “blooming haberdashery flaunted about Fred Hulbert’s esophagus”

- Neckties tied with a sixteen-inch difference between the two ends

- A ski sweater that “violates every last dimout regulation”

- The green tam (a type of millinery cap) “adoring the pate of Ray Schutt”

Aside from clothes, Tatler also went after hairstyles, citing the “bristle-top of Bruck,” the “musician’s coiffure of Shurtliff,” and the “frontal mop of Chuck Walsh” as particularly egregious. They ended with praise for student Dave Schick, who they declared an eminent student in terms of fashion with his dark green blazer, dark brown slacks, and conservative bow tie. “Would that there were more of him at Lakeside!”

In 1944, Tatler published an article titled “Dress Regulations Relaxed.” Detailed in the statement were the new customs of dress for Lakeside students, which included permission to sport the dreaded sweatshirts and sweaters. Tatler also seemed to have reversed their position on the formerly taboo items of clothing, declaring that “The looks of the student body is and has been very good, and will continue to be so.” Also in 1944, the idea of “cord-day” surfaced: the student motion to wear their dirty cords on Fridays. “Oh, what a thrill we will get to just walk down the main corridor of Bliss Hall, our well-stained ‘bellers’ flapping in the breeze,” one particularly enthusiastic writer penned.

The fashion-critiquing fashion of Tatler continued through the 1940s. In 1946, Tatler configured a new list of questionable fashion items, inviting students to voice their own opinions on the following (while also including Tatler’s fair share of opinions):

- John Rolfe’s yellow sweater and “those socks”

- That red ski sweater of Manson Harlan

- Those two “dog blankets” that are being worn as sports coats

- Ray Ryan’s brown hat, which “sure was a sad article of apparel”

- Hank Whitney’s new white sweater (“the best looking [sic] sweater in the school”)

- Jerry Barash’s new loafer coat

- That yellow rag that Bruce Sheppard uses for a tie

- “Everything that Bill Anderson wears” — “strictly red-hot”

Also deemed red-hot were the new basketball suits, the “flashiest suits that have ever played on our floor.”

Through the 1950s and 1960s, standards of dress shifted yet again, reflecting the attitude around fashion for the time. In a 1961 piece titled “Vernal Attire,” Tatler declared the year’s “legal dress” in a list of do’s and don’ts:

Do wear: Suntans (similar to military khakis) or polished cottons, cords, faded blue or tan jeans, Bermuda shorts with knee-high socks, sport shirts, clean low-cut tennis shoes, and sweaters worn over a shirt

Don’t wear: Shirts without collars, Bermudas without knee-high socks, regular blue jeans, and collarless sweaters not worn over a shirt.

Tatler also fought vehemently against restrictive fashion advice circulating at the time. In a short piece titled “Jeans Linked to Delinquency,” they commented on the contemporary news: the nation’s retail clothiers had found a link between blue jeans and juvenile delinquency, and they urged students to abandon their “sloppy dress habits.” Tatler, which consisted of students whose dress did indeed include the dangerous blue jeans, remarked “How ridiculous!”

Lakesiders continued to push for a looser dress code. In 1968, the article “This Time, Free Dress” framed the conflict as a battle for sovereignty, with the student body confronting the “austere and conservative senate.” The aforementioned student body soon “crammed the measure down the senate’s collective throat with a vote in assembly,” and overnight, the halls of Lakeside exploded into a self-expressive fashion frenzy — dirty tennis shoes, loafers with no socks, cords, sports shirts, and turtlenecks levis were among the many items donned in new and inventive ways. Tatler’s comment? “Anyway, the school hasn’t yet crumbled into its debris by the advent of such a tradition-shattering innovation.” And though the first battle was won, the war was not yet over; opponents of free dress believed it would lead to the “gradual decline of self-discipline” and criticized the loss of tradition. “If it was good enough for our fathers, isn’t it good enough for us?”

From the 1970s and on, fashion trends continued to grow and wane, though without the oppressive nature of the school dress code hovering over stylish students. In 1977 and 1978 Tatler re-explored Lakeside’s current fashion trends. The theme? Going to extremes to “achieve the ‘total look’ in non-conformity.” Replacing the ‘comfortably lived-in look’ of the past, which included cigarette burns, permanent staining, and fabric tearing (the modern replica of this would probably be distressed clothing), Lakesiders leaned into “imaginative attire.” Down pullovers, scandia clogs, and hiking boots consisted of the preferred footwear. The new trends necessitated three to four layers — five or six on cold days. Scarves should be hung around the neck with “no apparent purpose,” Tatler instructed. Individualism was all the rage, and so were distinct student styles; Tatler dubbed each with their own tongue-in-cheek moniker, with the “I-got-into-my-jeans-with-a-crowbar” look, “I-am-a-Preppie” look, “My-family-owns-a-clothes-store-but-would-you-ever-have-guessed?” look, and the “I-dressed-in-the-dark-with-both-hands-tied-behind-my-back” look apparently enjoying much popularity. Showing the ephemeral nature of trends, the following year, individualism had dissolved into several distinct cults of fashion—to be followed religiously. The “Genuine Organic” look, “Eddie Bauer Style” (hiking boots, wool socks, lumberjack shirts), and “Alligator” look (cord levi’s, moccasin shoes, alligator shirt) were all in style, but the “Seventeen” look took the crown with its chic white vests, string ties, and other items from the magazine Seventeen’s high fashion catalog.

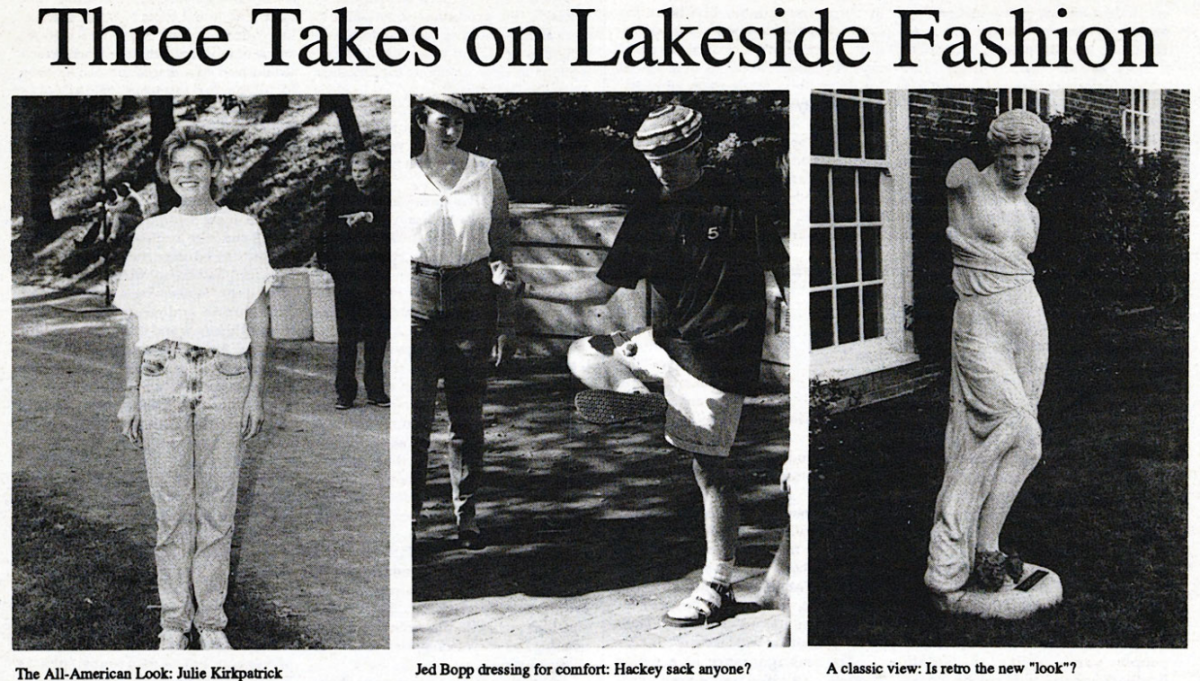

Fast-forward a couple of decades, and the “cults of fashion” had all but disappeared into a melange of diverse fashion choices. In 1993, fighting against Lakeside’s reputation of “preppy dressing,” Tatler declared the community “a wonderful pot pourri of various fashions.” All manner of clothing was in, from 5-inch platform shoes to tevas, patagonia and blazers, bell bottoms, and the 501 jeans. “One must not feel obligated to stick with one look,” writer Hillary Stamm reported.

A decade later, the lack of strict expectations remained true. “Our fashion is like Outback Steakhouse dining — No Rules, Just Right™,” Tatler wrote in 2004. “Stylish people can wear color-coordinated Abercrombie outfits, clashing prints, or bathrobes.”

Over the years, Tatler has been key in documenting Lakeside’s wild fashion history. From rebellion against a strict dress code and critiques of Lakeside’s odd and unique sartorial tastes, to the emergence of individualism and a fashion-diverse student body, the evolution of Lakeside attire has been—and will continue to be—a convoluted, fascinating, and unconventional journey. Clothing, hairstyles, and accessories reflect the environment and circumstances of the time—wouldn’t it be interesting to see what future Lakesiders think of our own fashion sensibilities?