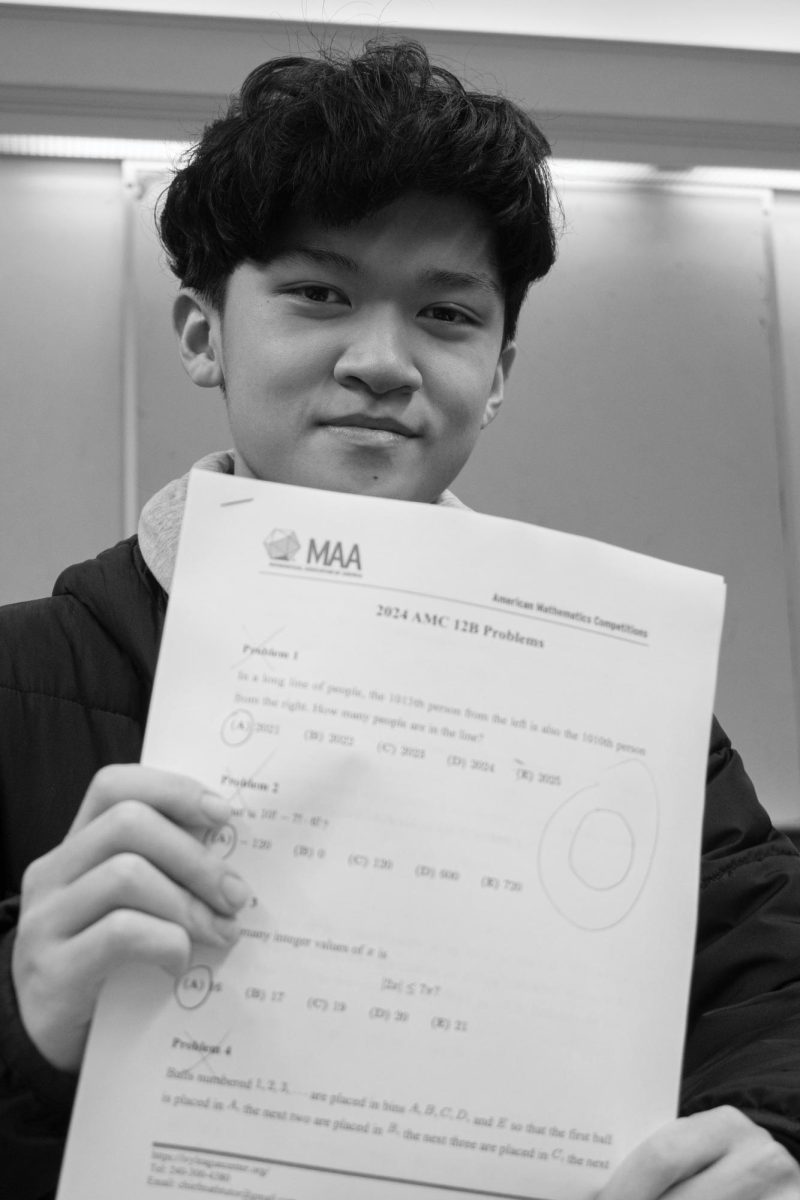

On November 12, I was privy to a historic moment in the history of math competitions at Lakeside: a new AMC record set by none other than Oliver C. ’25. He had told me about his ambitions for perfection at lunch the day before, and I expressed my reservations—I wasn’t sure whether it would really be possible.

But on Wednesday, Dean Ballard — a former Lakeside teacher and our school’s STEM competitions manager — emailed Oliver with his score: a perfect, unadulterated 0. Now, you might think that I’m just pulling your leg or playing an extraordinarily mean prank on my friend, but it is genuinely difficult to get a score of zero on the AMC 12.

The issue arises in the fact that the exam has 25 questions, each with 5 choices, where a question left blank is worth 1.5 points and a correct answer is worth 6. If you guessed randomly on all 25 questions, you should expect a score of 30 out of 150. The probability of getting a zero would be just 0.38% — or about 1 in 260. Therefore, to get a zero on the AMCs, you need to aim for a zero.

But why would anyone want to do that? For Oliver, the answer was simple: why not? He himself stated, “I could’ve probably managed a 70 or an 80 on that test had I tried my best — which is slightly below or maybe just on the cutoff [for the next round] — but no one, myself included, would remember that.” If he managed a perfect zero, though, it would be seared into the memory of him, his friends and the Lakeside math community.

During first lunch on that fateful Tuesday, Oliver descended down into the depths of past AMCs by not only practicing getting difficult questions wrong, but apparently also analyzing past years’ answers to determine which choices were the least likely to be correct answers. He told me later that “As and Es don’t generally appear that often as answers to problems 11 through 25. In this year’s AMC 12A, for example, A and E were correct answers to only 3 of the last 15 problems rather than the expected value of 6.” Intuitively, this makes sense — answers are generally ordered to be increasing, so A and E are extrema whilst correct answers are most likely somewhere in the middle.

Oliver’s diabolical plan, though, wasn’t entirely premeditated. He himself said that “it all arose as a joke I made with friends but slowly morphed into something more serious.” Even at the beginning of the test, he wasn’t sure whether he should aim for the AIME — the next exam in the AMC “series” — or aim for a zero.

Halfway through the exam, Oliver had solved nine problems, and he was fairly sure he couldn’t get more than eleven or twelve in total. So his mind switched into “shooting for zero” mode. He erased the nine correct answers he had on his sheet, bubbled in the incorrect answers and began analyzing the next sixteen questions. At this point, if he guessed randomly, he’d still only have a 2.8% chance of managing a zero.

Oliver had a much cleverer plan, though. He would try his best to test As and Es for reasonability and choose them if they appeared to be obviously wrong. This tactic fared well for questions 11 through 20. The last five questions, though, demanded something more akin to pseudomathematics: flat out vibes. But clearly, the blood coursing through Oliver’s veins was on the same spiritual wavelength as the Mathematical Association of America because he stands before us today with an ed square-shattering Lakeside record: zero points out of 150.

In reflecting upon his experience, Oliver offered a piece of sound advice to younger students: “don’t do what I did. If you can make the AIME or USAMO, if you can get a good score on the AMCs, please do not aim for a zero.” He added, “if you’re a senior on the AMC 12B, though, a zero might be worth it for the memes.”

He is certainly right that a score of zero on the AMCs is memorable, and he’s wise to caution us that we should pursue notoriety and humor over “doing well” in the conventional sense very sparingly.