I began reporting on the article you’re about to read in November of 2023 but if you were to ask when this story really begins, I might point you to August of 2005, when Indian American political commentator Dinesh D’Souza was invited to speak at Lakeside. In the past, Lakeside had been criticized for promoting overwhelmingly liberal values and now, as they looked for speakers as part of their Bebie Lecture Series, here was their chance to finally address those concerns. D’Souza fit the bill perfectly: a so-called “hero of the right” who among other views was infamous for his controversial views on affirmative action. Lakeside was willing to pay him $10,000.

But when faculty found out a few months later, they objected. Head of School Bernie Noe had originally called the faculty meeting to discuss what one white teacher called, in an email, “the fact that our community is losing some fantastic teachers of color at an alarming rate.” (That fall, two African American teachers had announced they planned to leave Lakeside, and the D’Souza invitation, I can only imagine, must’ve felt like a slight to that fact.)

Instead, the meeting became tense. Race, Equity and Justice teacher Chance Sims, who had been reading D’Souza’s work since 1995, disagreed with D’Souza’s invitation, later telling a Tatler reporter, “I did not want to give authority to the perception that some students are here because of their race or ethnicity.” In response, a white staffer admitted her role in asking D’Souza to come.

“Shame on you,” said Sims. Another white faculty member immediately rose to the woman’s defense in a physically aggressive manner. He was not asked to apologize by Bernie Noe. Sims, who is African American, was.

The following month, Sims sent a mass email to the school’s entire staff, which he called a valentine to one of the African-American teachers who had left that fall. It read: “After learning that the administration is spending hundreds of hours dealing with the D’Souza debacle, I’m left to wonder how this school might look if the administration spent hundreds of hours supporting retention efforts.” Sims’ email certainly had merit: after Lakeside rescinded the offer, newspapers from Fox News to The Seattle Post Intelligencer criticized Lakeside for its unappreciation of dissent, political wokeness, and “muzzling” of D’Souza. One local radio show called Lakeside teachers “intellectual cowards” and “tantrum throwers.”

But this isn’t a story about Chance Sims or the D’Souza scandal or even the racial discrimination lawsuit Sims would go on to file against Lakeside in the fall of 2006. This isn’t a story about the time in 2013, when Eastside Catholic High School vice-president Mark Zmuda was fired for marrying his male partner. This isn’t a story about the University Prep teacher who admitted to placing notes with anti-Semitic slurs in the school mailboxes of Jewish colleagues in 2018. This isn’t a story about when Bishop Blanchet 1997 alum Jessie Gifford married her wife and tried to submit an announcement to the alumni magazine, but was told “the archdiocese does not permit this type of information to be published in our Catholic school magazine.” This isn’t even a story about schools.

This is a story about the students who couldn’t — or were too afraid to — report on any of it. The students whose papers were shut down or whose funding was cut. The students whose advisors were fired, and the students whose advisors quit. This is about journalism.

For the past year I’ve spent reporting this story, I’ve referred to it as my “censorship piece.” But it’s more than that. It’s about relationships and what happens when those break down or are built up. It’s about how schools should have faith in their student reporters, and why student reporters have trouble having faith in their schools. It’s a story about the truth, and more importantly, it’s a story about when someone doesn’t want you to go looking for it.

————

Today, Martha Brockenbrough ’88 is the best-selling author of more than 25 books, a mother to two children (referring of course, to her two cats, although she does have a daughter), the past editor-in-chief of the Stanford Daily, an Editor of MSN.com, and the founder of National Grammar Day. But before she was any of those things, she was a student of Susan Saunders writing for Tatler in the late 1980s.

“This book is dedicated to her,” Brockenbrough says to me, reaching over her computer to grab a copy of Unpresidented, whose jacket reads, To Susan Saunders, who started me on this path. “It sounds simple to say she was a role model because she wasn’t just that … she showed me how I wanted to be in the world,” Brockenbrough continues.

Some could say this story starts even before D’Souza and instead with Susan Saunders. Up until the early 2000s, Tatler was run as one of three classes at Lakeside that focused on media literacy and the importance of the press, and Susan Saunders taught them all. While writing a Ph.D. dissertation on First Amendment rights, Saunders joined as Tatler’s faculty advisor in 1985 after making her position clear. “I had no interest in serving as a censor for the school,” Saunders told a Tatler editor in 2022. She quickly gained her reputation for what Brockenbrough describes as a deeply ethical teacher, stressing the importance of a free press, even at a private school such as Lakeside.

“She asked questions and made us think.” Brockenbrough pauses for a second before correcting “No, she invited us to think, because you can’t make anyone think.”

When Brockenbrough was offered a part-time position as Tatler’s advisor in 1992 after she graduated college, she gladly accepted the opportunity to return to the paper that had shaped so much of her high school experience. She later accepted the offer to be a full-time advisor in 2004.

But this time, Brockenbrough wasn’t prepared for how drastically things had changed since her time as student and as parttime advisor. “It became clear that the leadership of the school did not want a newspaper. They wanted a newsletter,” Brockenbrough remembers. And Than Healy, the Upper School director at the time, wanted an editor (someone to make decisions for the students, Brockenbrough clarifies), not an advisor (someone who helps their students).

If Lakeside was so concerned about teaching students how to be citizens in a democracy, then her job would be to teach her students how to be journalists in a democracy, Brockenbrough figured. “An obedient person that obeys even when they know it’s wrong is a fascist’s dream. So, I would like to be, you know, a fascist’s nightmare.” Unfortunately, Lakeside wasn’t ready.

“People love the idea of freedom of the press and they love the idea of democracy until it starts making them uncomfortable,” says Brockenbrough. And Tatler of the early 2000s certainly made them uncomfortable. When Tatler ran a story about a teacher resigning who had been found guilty of sexual assault, Brockenbrough once again faced pushback, this time from previous assistant head of school and current Open Window Head of School Elaine Christensen.

While Christensen declined to comment when I reached out to her, Brockenbrough recalls the conversation going like this:

“Is there anything factually inaccurate about the article?” Brockenbrough asked Christensen.

“No, there’s nothing factually inaccurate but it will harm the community,” she responded.

“So you’re saying the community will be harmed by something true?”

“Yes, that’s exactly what we’re saying,” Christensen answered. Brockenbrough disagreed.

“I don’t think schools should be in the business of describing truth as harmful … truth can be painful, difficult, challenging, embarrassing. Truth can be all sorts of things that give us all sorts of unpleasant emotions. But are we harmed about the way we feel about something? Or is the harm actually some other place?” Brockenbrough told me.

The censorship only worsened after the 2006 lawsuit was filed. In a letter from the editor in November of that year, Beatrice Liem ’07 recalls trying to report on the story but being cut off at every avenue with a, “Sorry, we’re not allowed to talk about this.” Later that month, Alumni Relations Director Allie Spies requested PDF versions of the September and October issues of Tatler to post online, which detailed the D’Souza scandal. When they weren’t posted, Liem reached out.

“The communications office (under the advisement of the school attorneys) decided that due to the lawsuit, it was best not to post the Tatler issues for now,” Ms. Spies was quoted saying in a Tatler article. As tensions rose at Lakeside, the internet was rising alongside it, and Tatler’s online issues, meant to be a way to spread student reporting beyond the community, were becoming an added concern for the administration.

Brockenbrough, once again, disagreed. “Lakeside invites alumni to football games and other school events because it is proud of what students do. When Tatler is excluded from Lakeside’s websites, it sends a message, to me at least, that Lakeside is not proud of this publication.”

Liem agreed. Something was changing at Lakeside for the worse.

“Incidents such as these indicate that it’s time for us to begin to ask questions … How far will these censorships go? Will we eventually have to remove that line in the gray box that says that Tatler ‘is not reviewed by the administration prior to distribution’? What about the phrase ‘intellectually independent’ on our website? Perhaps these are extreme examples,” she wrote that November, “but they are real concerns. If China can censor Google, the administration certainly has the power to censor Tatler, even if it lacks the desire to do so.”

Brockenbrough wasn’t surprised any of this was happening — her time at Lakeside had shown her the school wasn’t skilled in having sophisticated conversations — but the pushback was becoming too much. In December of 2006, she decided it was finally time to leave.

“I don’t want to send the message to you guys that when things get tough, you stop fighting. But I never know when I’m going to be called in to talk about some issue a parent has with Tatler. And I’m tired,” Brockenbrough told her class. When she made the announcement, a collective gasp punctuated her words. When the tears began flowing, EIC Liem made a startling “…discovery that there were no tissues in the room.”

About her leaving, Brockenbrough recalls a board member remarking that “she just wants to print whatever the students want.” One of her students, Paul Menter ’08, had a different interpretation: “How is it that a school, in its attempts to provide us with the best education possible, has failed to keep one of the sources of this education?”

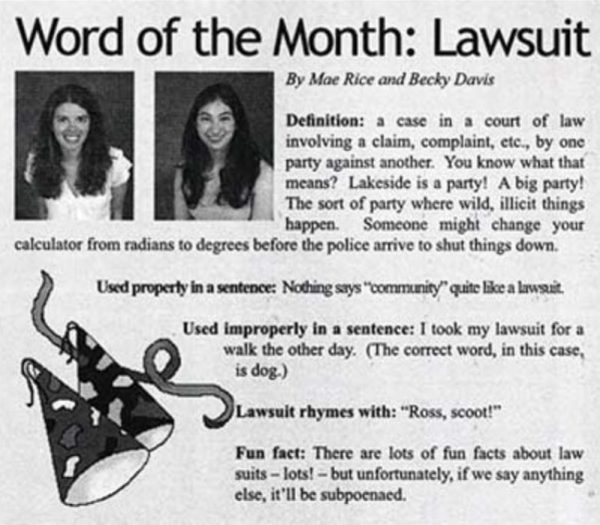

That issue, the word of the month for Tatler was “lawsuit.” When Gil Aegerter, News Editor of the Seattle Post Intelligencer, was approached to fill in for the rest of that school year, he knew he would be in a difficult position. It wasn’t that he didn’t have the experience for the position — as a former editor of the public radio station KUOW, he had more than his fair share of journalistic knowledge. He would be in a difficult position, he said, because the students themselves were in a difficult position.

Almost immediately, Aegerter felt suspicion from his students. He didn’t blame them — after all, here was a group of students who had gone through two advisors that year already (Brockenbrough and an interim advisor), and it wasn’t even February. It helped that Aegerter’s wife, Dr. Lindsay Aegerter, was a beloved English teacher at Lakeside. But still, after so much hardship, the question lingered. After all, it was her they knew, Gil Aegerter reminds me, and not him.

“What kind of person was I going to be?” Aegerter recalls. He understood that a lot of the kids respected Brockenbrough, and felt hurt over the circumstances of her leaving. And above all, he knew Brockenbrough’s reputation as a teacher who cared about the ethics of journalism and what was right. “You know going into [this job] that you’re going to be seen as this person chosen by the administration to be not that — which is a little disturbing for me.”

The answer to Aegerter’s question, and perhaps what the students needed after a year of the administration avoiding their questions, was honesty. After a month, Aegerter addressed the elephant in the room.

“You guys don’t know me, and I know I’m coming in under unusual circumstances,” he told them during one meeting. “But I’m going to act on the principles that I operate on, and I’m going to try and help you be better journalists.”

It must have worked, because years later, when Jackie Steves ’08, the Editor-in-Chief that year, describes her time with Aegerter, she laughs when saying she doesn’t even remember being originally suspicious. “It doesn’t mean there wasn’t any doubt,” she adds, “but what dominates my memory of him is he was an inspiring teacher who we learned a lot from.”

Aegerter was no exception to the fond memories Steves has. A teacher now herself at a religious school in Los Angeles, when looking back at her time on staff, even during the lawsuit, she envies Tatler’s freedom to be “bold and courageous.”

“Freedom of expression [at my school] is non-existent,” she says, “compared to Lakeside.”

When the 2006 lawsuit was filed in the fall of Steves’s junior year, she had the chance to interview Bernie Noe. Tatler, which Steves remembers “communicated the importance of journalists being courageous in terms of wading into difficult issues” under Brockenbrough, had prepared her well. Still, when it came down to it, Noe said he couldn’t comment on the ongoing lawsuit. Steves didn’t press, even though she says she wishes she did.

Students and teachers, including Aegerter, weren’t privy to everything. Noe had never really filled him in on the details of what had transpired in September; he simply knew there had been some tension over stories and tension over the lawsuit at Lakeside. Steves, despite having been taught by Chance Sims, was left in the dark about what was happening — a challenge exacerbated by the ongoing lawsuit. It was even a surprise to her when Brockenbrough left.

Nevertheless, both Aegerter and Steves agreed years later that they didn’t face any direct censorship by the administration. There had been some close moments: in previous years there was an issue with senior quotes in the yearbook and during Aegerter’s time, the administration became concerned after one of the students did an investigative piece testing the water around campus during nationwide scandals of lead in water. Even if there was, Aegerter made sure they were prepared. He gave advice on proper journalistic conventions, took them to the Seattle Post Intelligencer newsroom where he was simultaneously acting as editor, and empowered students to practice real journalism, according to Steves.

In fact, she was so inspired that she gave Aegerter a note at the end of the year saying she was going to major in journalism. Aegerter, who had majored in photojournalism at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, freaked out and told her not to make the same mistake he did.

Almost two decades later, Steves laughs at the memory. “I guess he was right — I majored in Poli-Sci.”

Aegerter left at the end of that spring. As the long school year came to a close, it was time for someone else. What Lakeside needed was, in Aegerter’s mind, someone who hadn’t come to the position under the shadow he’d inherited. It would be a new start, a new year, and a new group of kids. At least for now, it seemed like the period of Lakeside censorship would be coming to a close.

————

When Washington state became the 14th state to sign on to the New Voices Act in 2018, student journalists rightfully celebrated. The state law established a clear relationship between public school administrators and students, spelling out when a school could step in with censorship (e.g., for health and safety reasons, libel, etc.) while granting protections for student papers’ advisors. Essentially, the new law protected student journalists’ rights to free speech.

But for the students of independent schools in Washington, nothing changed. The closest thing these journalists had was a non-binding contract made available by the Private School Journalism Association (PSJA). Drafted by a team of lawyers, journalists, and specialists on student press freedoms, the statement is some version of an agreement between a private school and its newspaper that limits prior review (a school’s ability to look at the paper before publication) and prior restraint (a school’s ability to change content in the paper based on their review). In 2018, no school had yet to sign on to it.

Five miles away from Lakeside, University Prep was trying to change that.

————

At a coffee shop in Tacoma, Sydney Goitia-Doran quickly reveals herself to be easy-going as she invites me to sit down beside her. This year, she’ll be a sophomore at Howard studying environmental journalism (in fact, she wears her hoodie proudly during our meeting) and is the first person in her family to go to a four-year college. But she started her journalism career years ago in middle school at University Prep.

Back then, Goitia-Doran’s main goal was not student press freedom or environmental journalism, but to fit in. Having come from Rainier Prep, a charter school in the south end made up primarily of students of color, she found herself in a new school, in a completely different environment where 60 percent of students were white.

UPrep’s newspaper, The Puma Press, was no different at first. As one of only two freshmen in a class full of upperclassmen, at times she felt the paper was one giant friend group. “I wanted to be them, but I also felt left out,” she remembers. It was this feeling that was at the forefront of her mind as she was chosen to be EIC senior year. “I remember what it was like freshman year, and you [freshmen] are not being left behind.”

Perhaps that was part of why Goitia-Doran immediately pointed to herself in the fall of 2023 when UPrep’s newspaper advisor Scott Collins asked who would take on the lead of getting the administration to sign the PSJA statement.

This wasn’t the first time that a policy like this had been proposed at UPrep. In 2018-2019, the then upper school director didn’t believe the agreement was appropriate. When the two student editors, who Collins describes, admiringly, as “basically 35-year-olds,” were rejected, Collins said he and the upper school director fundamentally disagreed. Covid took care of any progress with proposal number two, and while the debate around the third proposal a year later was closer — then-senior Parisa Harvey wrote an op-ed for The Seattle Times urging UPrep to sign on — it wasn’t close enough.

Both Goitia-Doran and Collins agreed that the third proposal lacked sufficient detail. When a misunderstanding between something Harvey wrote in her article and the head of school occurred, Collins clarified things on the back end, “but it made me think, this door’s not shut.”

At the same time, relationships were straining not only in the school but in the surrounding neighborhoods. As UPrep set out to construct a new building, neighbors began to voice concerns over the school’s lack of consideration and organized protests. But as neighbors’ voices grew, those of The Puma Press fell silent. Staffers were told not to interview certain neighbors out of fear it would make the school “look bad” (“We aren’t [public] relations. Fluff yourself up on your blog or magazine,” Goitia-Doran adds), controversial quotes and interviewee subjects were pulled, and when asked who they were allowed to interview, students were given a list hand-picked by UPrep administrators. And this, Goitia-Doran notes, was a school that preached about upholding values of courage and honesty.

This time, with a new head of school and upper school director, something in the air felt different.

This proposal had a shot. For as long as Goitia-Doran could remember, brainstorming discussions within the paper not only involved asking “who, what, when, how and why” but “how would so-and-so person react to this?” The additional layer of considerations wasn’t just causing social stress of having to navigate administration tensions while trying to run a student paper, but professional stress as well; should the administration choose to pull a story or reframe the way it’s written, press deadlines would be pushed back, ultimately pushing back their deadline agreement with Pacific Press Publishing. It was time to change that.

“At the end of the day, we don’t want to make the school look bad. We just want to tell the truth,” says Goitia-Doran.

For Goitia-Doran, the formal document was much more than a contract or a statement: it was an issue of mutual respect, and trust to represent their community well. “You shouldn’t be uncomfortable with the people who are uncovering the truth,” she adds.

Still, despite this conviction, Goitia-Doran and Collins weren’t sure which way it would go when they were preparing to present their case near the end of May, 2023.

In the weeks leading up to their final meeting, it had been hard to find the available time to rehearse. For his senior project, one of the Puma Press staffers was directing the school play and Goitia-Doran was the lead. The meeting falling so close to prom and graduation required Goitia-Doran to spend her afternoons trying on her dress, cap, and gown, running to rehearsals, and then running to Collins’s office.

“This isn’t going to go through,” she remembers thinking. Collins agreed. “I’m a skeptic, like any good journalist should be, and I was honestly like, ‘I don’t know if this will happen,’ especially when we had made it through the first semester and nothing had happened.” Not only that, presenting this policy in May of Goitia-Doran’s senior year meant there was a tight turnaround. It was now or never, it seemed to both of them.

Despite everything, they were prepared beyond belief; current EIC Carter Headstrom still has vivid memories of seeing the seniors rehearse their scripts over and over before class.

In the end, they delivered their case flawlessly. The kicker? Referencing the school’s own motto to highlight the hypocrisy of a position against the statement. “If the school is aligned with all these values, then there shouldn’t be a problem with anything we publish,” Goitia-Doran tells me, recalling.

Scott knew by reading the room. “One point, I can’t remember when it was, the third time we had referenced back to the school’s words, she just sort of laughed … but you have to know our head of school. I knew it was a good thing because it was a laugh of, like, ‘Oh my god, look how much they’ve put into this, look how much digging they’ve done, look how thorough this is.’”

“Okay, where do I sign?” Head of School Ronnie Codrington-Cazeau asked. As soon as the door shut, the newspaper staff exploded into cheers. Goitia-Doran laughs while remembering how they kept repeating, “We are the first. We are the first. We’re the first.” “It was just a class. We could’ve taken the elective and never come back. But we created a legacy,” she tells me.

————

Around the same time the first proposal was being made for student press freedoms at University Prep, Lakeside was finding its own footing with how to respond to controversy on campus.

It was 2021 and a former student had just posted on Instagram about how a current Lakesider had sexually assaulted her. As students observed the alleged perpetrator continuing to walk around Lakeside’s campus, a general consensus formed among the students: the school had done nothing about the incident or the allegation.

The student reaction reflected part of a bigger problem at Lakeside. The belief among a lot of students was that at Lakeside, “things were very much handled under the rug.” And when it came to problems like sexual violence, students recognized what Dash Barnett ’21, now a senior at Georgetown, calls a “hypocritical, half-assed” stance on the issue. “People really saw this hypocrisy from the administration because you have what people saw as token gestures, these sexual violence prevention (SVP) workshops, and then if someone actually committed sexual violence, they weren’t getting thrown out of school,” he explains. (It’s worth noting that since then, SVP workshops have been completely redesigned). Nevertheless, a bigger picture emerged as well: at Lakeside, there was a culture of silence.

As soon as the Instagram post came out, Barnett knew he wanted to write a piece about it. Over the years Tatler had garnered a reputation for not being as serious or as effective as it could’ve been. Here was his and the rest of the staff’s chance to change that. “One day, we were like, ‘F*** it, let’s actually do this,” Dash remembers.

Their initial idea was to do an investigative-type exposé, but they quickly realized they would have run into several legal and privacy issues with that approach. Instead, they published an article that was clearly about the case without referencing it directly. “We do not want to further harm those who we are writing this to support,” they noted in their article.

The article idea took the form of a letter: “Speak Up About Lakeside’s Rape Culture: A Message to Students From Senior Tatler Staff.” “As we in the class of 2021 move into the final weeks of high school and the last round of Lakeside workshops, our message is this: if we do not believe that the administration has handled the situation correctly, it is up to the students to take steps in the right direction.”

It was a sunny day towards the end of May when they passed out the letter by hand, going from classroom to classroom and from person to person on the quad to distribute it. And almost immediately they were called into a meeting with then-Head of School Bernie Noe.

“[Tatler’s EIC] and I had been talking about our fears that [the letter] would lead to consequences with Tatler,” says Barnett. Tatler had been shut down before, briefly, in 2017 because of inappropriate messaging that had made its way into a student-submitted senior wish list. But part of them was, at the same time, excited. At least this meant on some level the school was taking the right step toward progress.

Barnett describes the meeting as not warm, but not exactly cold either. It became pretty clear that Noe was frustrated and felt that the paper had been unfair — that the students were rushing to judgment without any way of knowing all the facts. “The administration’s tone was not ‘thank you for bringing this to our attention’ — it was ‘f*** you for writing this’ in the kindest way possible.”

But their letter, on some level, worked: the school held a school-wide meeting over Zoom to discuss their sexual assault policy. Students were generally still frustrated — what they wanted was not more transparency, but the school to expel the assaulter, a specific sign of commitment that the school would take action in cases like these. But, “I do think they tried,” Barnett adds. “I’m not sure to what extent they did, but they at least tried to do something.”

It was true — especially considering the ways in which Tatler had been shut down in the early 2000s, the process of the letter and the school’s reaction looked very different. Despite both instances involving an ongoing legal investigation, there were notable differences in how the administration chose to give its feedback. Noe even pointed Barnett to the school’s lawyer for more information. And — suggesting the ultimate mark of a successful free press, though the cause and effect can’t be proven — the school soon began implementing comprehensive changes to its sexual violence prevention program.

————

When I began this story, I told you it was going to be a story about trust. As a former reporter, section editor, and now co-editor-in-chief, I reassure you that the Tatler of today, supported by new administration members, trusts in the school, at least as much as any student paper can. The people who we don’t trust now, instead, tend to be ourselves.

“We find ourselves self-censoring more than anything,” Goitia-Doran said.

Unlike forms of explicit censorship, there’s nothing tangible to point to when it comes to self-censorship. Sometimes, one theory goes, that when it comes to politically conservative viewpoints, Lakeside’s — and to that extent, Washington’s — overwhelmingly liberal population has created an environment where dissenting opinions remain unspoken.

That appears to be the case at The Eagle Eye at Eastside Prep in Kirkland. “Maybe part of the reason why we don’t have so much controversy is that everybody generally agrees on certain things,” former EIC Diya Nahar tells me. “I think it’d be very different if you’re in a different state.”

Consensus in newsrooms sounds great — but how much of it is imagined because those with other opinions are scared to speak up?

Sometimes, when we come together as a newspaper staff on the first Tuesday of each month, it is the knowledge of Tatler’s past that dictates our future: because we know Tatler has had a history of censorship in the past, there hangs this looming question of “When next?” As Brockenbrough reminded me, “If they make you uncomfortable enough, they don’t have to say don’t do it.”

UPrep EIC Connor Headstrom agrees. UPrep’s ongoing construction with its new building (dubbed ULab) was meant to provide more space to students on campus, but instead, Headstrom describes a reality in which the school over-admitted students to the unfinished building, leading to a crowded campus. The editorial he wrote ended up occupying a middle ground between criticism and praise, but still, Headstrom said he “could’ve been harsher.” He felt like in some ways he held himself back.

So what’s the solution to a problem you can’t point to?

Beyond the PSJA statement, it begins with trust. “The students should feel like the administration wants them as part of the community. This administration should feel like the students are helping build that community,” Lakeside’s Upper School Director Ryan Boccuzzi tells me.

In January of 2023, after months of interviewing, researching, and studying, I bring up the idea for the PSJA proposal at Lakeside in a meeting with Mr. Boccuzzi, alongside Tatler’s editors-in-chief, Lucy Kaplan ’24 and Zane Reed ’24. We’re in the middle of a classic Seattle winter, but the sun is shining over McKay chapel as we walk out of the meeting onto Red Square.

“How do you think it went?” Kaplan asks.

————

My English teacher at the School for Ethics and Global Leadership and former Lakeside history department head Colleen Kyle used to ask our class each day, “What do you owe to yourself and others?” Some students made the case that we owe each other compassion. Others took a more controversial route, and said we owe each other nothing. As an English student, I struggled with the question throughout my semester away, but as a journalist, the answer is clearer than ever. What do we owe ourselves and others? The truth. It really is as simple as that.

The question for journalists at private schools is not, “What do we owe ourselves and others?” It’s in our obligation towards truth, and will our school support us? What Liem said when Brockenbrough left in 2006 remains true: “All that I know is that Martha has left us a legacy of searching for the truth. And it is our duty to preserve it.”

As I write this in the fall of 2024, I am the same age that Sydney Goitia-Doran was when she proposed the PSJA statement to UPrep. Will Lakeside sign on to the PSJA statement? Will that be a part of the legacy this era of Tatler leaves? That is left to be answered. What’s more important are the questions underlying the statement: In its search towards truth, can a school trust its students and can its students trust their school?

And, when it comes to asking the hard questions and publishing articles even when they’re controversial, when it comes to seeking the truth, how much can we trust ourselves? I suppose it’s up to us. I suppose at the end of the day, what this story is about is really up to us as well.

Correction 1/24/2026: The article previously misspelled the name of interviewee Sydney Goitia-Doran. The error has been corrected.