“Parking is a huge problem [here] because once you get your license, you have to ask, where do you park?” says Mia L. ’26 from Seattle Prep, the same high school which boasts a two-story underground parking garage.

Five Seattle area high schools from Central District to Haller Lake battle the all-too-common 21st-century issue of not having enough parking space for their students. But what does parking look like for students specifically?

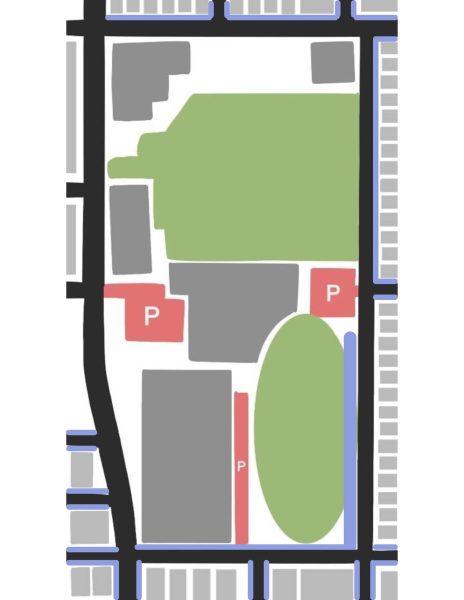

LAKESIDE SCHOOL

LAKESIDE SCHOOL

Lakeside does a “pretty good job” with parking accommodations, says Henry J. ’25, a two-year driver at Lakeside. This “pretty good job” refers to Lakeside’s four parking lots available to students with parking passes: the gravel lot by Stimson Field to the west, the lot adjacent to the Paul G. Allen Athletics Center in the north, the senior-only parking strip to the southwest, and, until construction on the new building began this summer, the grass softball field — 320 spots in total, Henry estimates.

The extensive parking space means Henry always parks within three blocks of the school. “I usually arrive around 8:20, but if I’m running late, I can usually get a spot [in a parking lot] right at 8:30,” he notes.

Henry transferred from Ballard High School to Lakeside his junior year and points out a big difference between public and private school parking: “Ballard only had faculty parking. It’s a much bigger school, and they didn’t provide students with anywhere to park.”

Despite the varied accommodations, Henry still has a few suggestions for Lakeside. It starts with drawing designated parking lines in Stimson. Next, pave over the potholes and make the parking lines wider in the AAC lot.

“Both those changes could happen feasibly in a year,” he says.

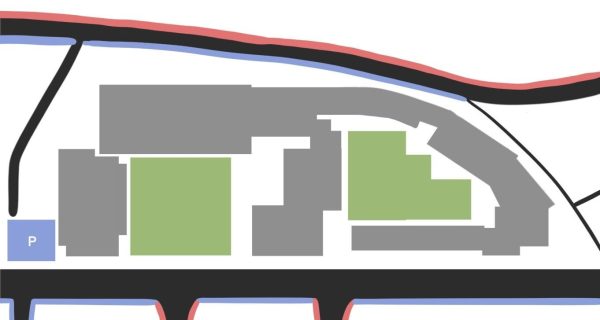

SEATTLE PREPATORY SCHOOL

Seattle Prep might be well-known in the junior parking world for its fabled two-story underground parking garage. Turns out, the only mythical thing about Seattle Prep’s parking lot is its convenience.

Mia L. ’26, a rising junior at Seattle Prep, brought up how cramped their parking lot was in the second sentence of describing how she parks. The first one acknowledged the existence of said garage.

“It’s pretty small and tight. There’s a lot of accidents that happen there,” she says, referring to her annual school estimate of 2-3 scratches. “Backing out is a chore. I know someone in my grade [who] scratched my soccer coach’s car on the first day [of school].”

Mia explains that garage parking privileges are acquired through an annual application. Priority goes to long-term injuries, students who live 30 miles or farther from school, and then number of students in carpools.

Even then, “all the teachers park underground [too], so there’s barely any space [for students],” she notes.

Like most students, Mia couldn’t land a spot in the garage. As a result, she arrives 30 minutes before school starts every day just to find a spot in Seattle Prep’s cramped neighborhood.

“I park every day, so it is a struggle [to] force myself to get up and get a parking spot early,” Mia points out. “But that’s kind of the reality, ’cause if you’re coming even 15 minutes before school, there’s not going to be spots.”

In the end, Mia claims that parking is not “a huge issue” for her despite the long distances.

“I’m good at getting there early. I’ve gotten the hang of it, and I’m fine with walking.”

THE BUSH SCHOOL

“The parking situation is very controversial,” says Emerson WG. ’26, a rising junior at Bush who has not yet started driving.

Once students obtain their parking tag, Bush offers an indoor garage mainly reserved for carpooling students. They also have unofficial streetside senior parking enforced through post-it note vandalism against non-senior cars, and a vast network of neighborhood parking. Emerson estimates 100 total spots for students.

But one must “tread” lightly when it comes to parking, as Bush is “very strict on parking,” says Emerson. “[Neighborhood] streets fill up completely during the day, and then people [who live in these neighborhoods] come back to their house, and they have to park far away,” says a rising junior driver at Bush who spoke anonymously due to fear of retaliation. Then, “[the neighbors] request we ban parking on that street.”

The stakes were higher than ever before during the transition to Emerson’s sophomore year. At a schoolwide presentation, the dean of students announced that thanks to “outrageous” parking violations and neighborhood complaints, Bush was imposing a $100 fine for misparking.

“It was a surprise to many people. [Then], it became ang[er],” Emerson recalls. “$100 is not the same for every person,” he adds.

Another reason for outrage, Emerson states, is how “many people are very opposed to the idea that people can’t park in certain places. It felt like the parking was very strict.”

Post-presentation, there was a lot of negative vocal reaction. “This has happened multiple times: someone will [say] ‘The parking situation’s pretty bad, how can we improve it?’ and then faculty will say ‘We can’t. We have to prioritize all these other things,’” says the anonymous source. “There isn’t really a good solution. I think it’s frustrating for both faculty and students.”

But the future isn’t all doom and gloom: an expansion of Bush’s bus routes is scheduled for this upcoming year, and the anonymous source is hoping the situation will be “better if people actively choose to take the bus.”

They add, pessimistically, “Other than that, I think it’s gonna get worse.”

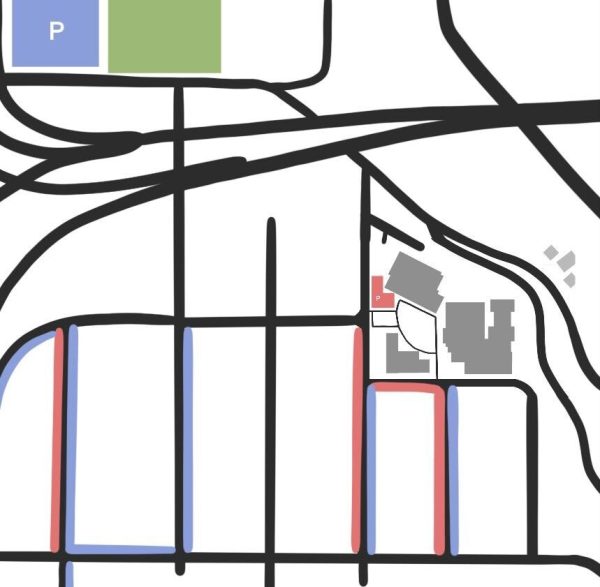

LINCOLN HIGH SCHOOL

“Lincoln’s the marijuana of schools,” says Wilbert Z. ’26, a rising junior at Lincoln High School. “[We’re] just chill — we don’t have as much stuff going on,” he quickly clarifies. He’s not a driver or a smoker, but he has never seen his friends have trouble with parking.

Similar to Ballard, Lincoln has a parking lot. For faculty only. Aside from “one small row of parking spots behind the school,” around 50 spots, students flock to the neighborhood streets to plop their car down.

Even though there are 400 students per grade, Wilbert claims “you can usually find a spot within a block away from Lincoln.” But since last year’s smaller 300-person senior class graduated, congestion may be an issue this year from the 100-student increase.

Another problem seems to be the city’s parking enforcement officer who roams around campus.

“They’re really anal about the smallest things — it’s a $400 ticket if your tires are a few inches over,” Wilbert exaggerates. “One of my friends got a massive ticket for having their tire over… To be fair, it was in the disabled parking spot.”

Again and again, Wilbert insists there isn’t much to parking at his school. “Worst-case scenario,” he says, “there’s a Walgreens less than a block away with a parking lot. FamilyWorks [Food Bank] has their parking lot — it’s literally part of Lincoln.”

The true worst-case scenario, though, is Woodland Park by Green Lake, five blocks to the north. “It’s a short walk with a crap ton of parking, [but] most people don’t have to park that far.”

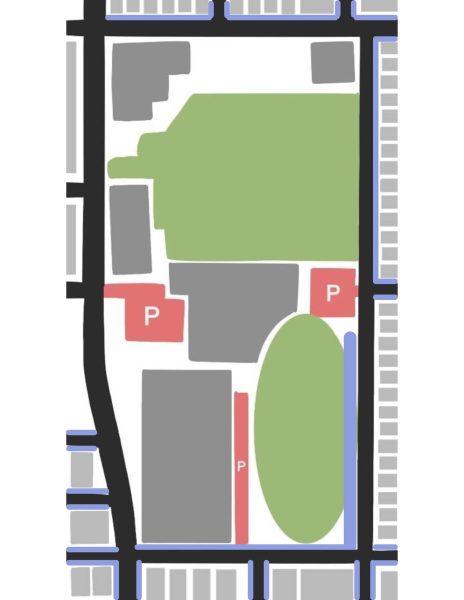

GARFIELD HIGH SCHOOL

At Garfield, student parking is just like their football field: not part of Garfield’s property. Instead, the 90100 spots of angled parking that line the east and south sides of the school are what students race to secure. Otherwise, it’s to the neighborhood for them.

Anna D. ’25, a rising senior at Garfield, doesn’t like that the parking spaces are angled. “The main problem with the angle parking is people take up like two or three cars worth of space just by going not sideways,” she complains. “I walk by a lot of really bad parking jobs.”

True to her word, @ghspoopyparking, Garfield’s Instagram account for shoddy parking, has sights that exceed the worst teenage parking imaginable. A quick scan presents kissing bumpers, cars angled opposite from adjacent cars, and an entire automobile situated above the sidewalk.

Every day, Anna has to arrive at the nearby neighborhood 20 minutes before the bell and find a spot. “Some mornings I get there late, and there’s a bunch of parking available. Sometimes, there’s no parking.”

Even then, parking has never been too much of a pain. Three blocks to school is her usual distance, and four blocks if she’s late.

As for improvements in the near future, Anna sees none.

“I don’t want to say no one cares,” she says. “I think we all would like parking to be better, [but] there’s not much to be done, and so it works out the way it is.”