One of Lakeside’s most important weeks — full of speeches and stakes — finally came to a close in March: presidential election week. In the midst of the busiest time of junior year, seven capable candidates did everything in their power in hopes of being elected student body president or vice president. But for the first time ever, their competition wasn’t their biggest threat to office. On the contrary, the lack of ability to campaign was.

After last year’s presidential candidates were called out for using an excessive amount of paper in campaigning, Lakeside administration took matters into their own hands and modified the rules to ensure that campaigning was equitable and sustainable.

This year, candidates were limited to just four methods of marketing themselves to the school. First, a single page on the StudGov “Voter’s Guide,” where candidates could reveal a little bit about themselves, explain their plans for the school, and convince students why they should be elected. Next, candidates had the opportunity to post not two, not three, but one singular image on StudGov’s website as their only means of communication through social media. Any other posts, tweets, or even TikToks were strictly prohibited with the penalty of disqualification. Candidates were also limited to 20 posters to post in various locations around campus — less than last year— and a single five-minute speech.

In Ulee K. ’25’s opinion, “with the current restrictions, there aren’t many opportunities for campaigning. So this puts us in a very limited position.” Nikhil D. ’25 adds his disapproval, saying, “We have very specific [rules] in the [Lakeside Student Government] constitution. It’s very tough; I don’t like that.”

To give some merit to the campaign restrictions, Samiya S. ’25 responds that the new guidelines make it more equitable for candidates to run. According to her, in other private schools, presidential campaigns became a game of “who’s daddy is richer” because students could spend money on campaign paraphernalia. At Lakeside, thankfully, even though we may not be seeing students posting on social media, at least we aren’t seeing candidate’s bobbleheads and flags.

The first declaration of presidency that hit school wide was StudGov’s brand new voter guide. For many, this was a good way to inform students about their ideas and initiatives. Rohan D. ’25 cites this as helpful, saying it’s “difficult to have someone who’s just standing around or walking through a hallway to really read something for, you know, a full three or four minutes. That’s why the voter guides are helpful.”

In general, the format for most of these voter guides tended to start with a quick introduction, an overview of the candidate’s expertise, and any projects they were planning to forward. A common trend within the guides was bolding any phrases or ideas that candidates wanted voters to remember.

Next, the posters. With just 20 posters, candidates had to choose wisely for their themes. From New York Times Connections to BeReal, from baby photos to Barbie, the vibe of posters had to be varied and creative to appeal and deliver a message to the largest number of students with a multitude of interests.

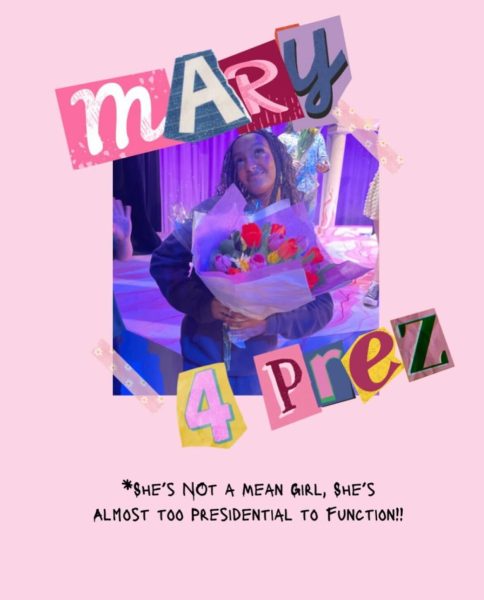

For Akal S. ’25, her poster was meant to be a “little bout of joy.” For Ulee, his goal was to present himself as a candidate that was “charismatic, funny, and relatable to the student body through common movies and [media]” Thus, he decided to choose an “Avatar: The Last Airbender” theme, as well as a funnier “escape the matrix” joke. Similarly for Mary Y. ’25, she utilized Mean Girls and Gossip Girl as a way of presenting herself as lighthearted and relatable.

“There has to be a balance between getting information across, and for lack of a better term, ‘staying with the times’ — something that people can resonate with, and also being straight to the point, [without] not too much text” says Aanika T. ’25.

Nikhil highlights the importance of being yourself in the posters, mention- ing, “I want people to know who I am at the end of the day, because that’s what matters when they go to vote — they need to know who you are.”

He also points out that in addition to being genuine, “you want to be unique so people can remember you. For example, everyone has a different kind of theme with their posters.”

Ava L. ’25 went with a different strategy of playing the memorability factor: “My biggest thing with campaigning before the speech was visibility with my posters. It’s not to necessarily have a message or a distinct ‘here are my ideas and here’s what I’m going to do for you.’ It’s about instant recognition like ‘they’ve seen that face before; they’ve seen that name before.’ So when I go up to give my speech, there’s already a sense of — maybe not trust — but at least some familiarity.”

Within the realm of introducing themselves, candidates also targeted frequently visited areas and tailored posters to those specific locations. For example, Mean Girls posters in St. Nick’s versus tennis posters in the AAC.

“Putting your posters up is like a large game of chess,” says Ulee, “You have to understand where all the foot traffic is. Because tons of people are always drinking at water fountains, that’s a large area that I’m trying to target.”

However, the grand finale came down to the speech. With 300 seconds and the entire school as an audience, candidates had to convince the entire school why they were the best choice for president. Since a majority of students might’ve not known the candidate well prior to this, “everyone was kind of banking on that to be their opportunity to really get their moment to shine” says Ava.

“There’s very limited time and space; I think that puts a really great emphasis and almost pressure on the speech to be really good,” says Aanika.

Most candidates listed their experience, their vision, and something memorable, such as a backflip or even a marriage proposal to the school.

However, candidates chose to execute their speeches in varying ways. Ava wanted to present herself as “a good, solid person. Just nice, friendly, approachable, but also firm [and] confident in my convictions, and capable.” Therefore, she went with a more “flat

and serious” approach. On the other hand, Akal went with a more lighthearted, emotional appeal. “Adding onto that message of inclusivity and kind of like compassion towards one another, I just want to show people that even though I’m very far away from our campus at Lakeside, I still have a commitment to the school.”

But while candidates poured their hearts and souls out for the speech, with some working on it since the start of junior year, many candidates faced one big issue: the number of people running.

For this year’s elections, the administration changed the rules so that instead of presidential candidates having to have served junior year as a rep, candidates “must be members of the rising senior class and have served at least one year on StudGov.”

While 75% of interviewed students agreed that the change was a good decision, as it allowed more diversity of candidates, it made it more difficult for the candidates to grab students’ attention. Instead of 20 minutes total of speaking, seven speakers were lined up back to back for a total of 35 minutes of speaking.

“It’s still seven [speakers] back to back to back. With all the regulations really, you can only do what you have control over. And I think everyone put a lot of time in [their speech],” says Ava.

Ulee adds on, noting “having seven candidates is a lot more difficult to win than having four different candidates.“ After all, “you can’t make yourself stand out in a group of seven people who’re all trying to make themselves stand out,” says Ava.

Besides the provided resources, candidates asked for more chances to connect with the school in lieu of the strict week-long window of campaigning. “I’d like to be able to talk to people more often,” says Mary. “Years before, I saw that we could do more papers and posters… It felt more conversational.”

Adding on, she points out that “while I understand the sustainability aspect of it — I really do think we should protect that — even if it’s not fireworks, [I want] an assembly where we can sit down, talk to people… At the end of this, the only thing I want is to feel satisfied that people knew who I was.”

In the end, after all the strategy and thought put into this election, another question arises: Is campaigning even worth it? Ultimately, some believe it isn’t about who you are in the week before the election — it’s about what you are as a person overall.

Rohan suspects “our grade had most of their votes decided before the election.”

Additionally, plenty of students would argue that, in the end, elections are really just a popularity contest. But incumbent treasurer Ava says otherwise.

“Popularity contest seems a bit like the wrong word to use, but it’s a lot about how much reach you have within the school community. Campaigning begins the first day of your freshman year when you walk into the doors of your first class.”