Content warning: This article contains mentions of racially motivated violence.

In 1896, gold was discovered in northeast Oklahoma — black gold, that is. One of the richest oil deposits in America was discovered on the Osage tribe’s land, briefly making them the richest people per capita on the planet. But with this wealth came evil, and in 1921, the Osage Reign of Terror began. Starting with the mysterious disappearance of main character Mollie Burkhart’s younger sister, Anna Brown, members of the Osage tribe with rights to the oil money began turning up dead. Those with oil money, known as headright-owning Osages, were the only ones who could collect the profit, with the exception of their spouses. So, it was no wonder that settlers – primarily white and male – flocked to Grayhorse, Osage County to marry. Thus began the race by a powerful white family to funnel all of the Osage’s headrights to Mollie Burkhart, wife of a white man, Ernest Burkhart.

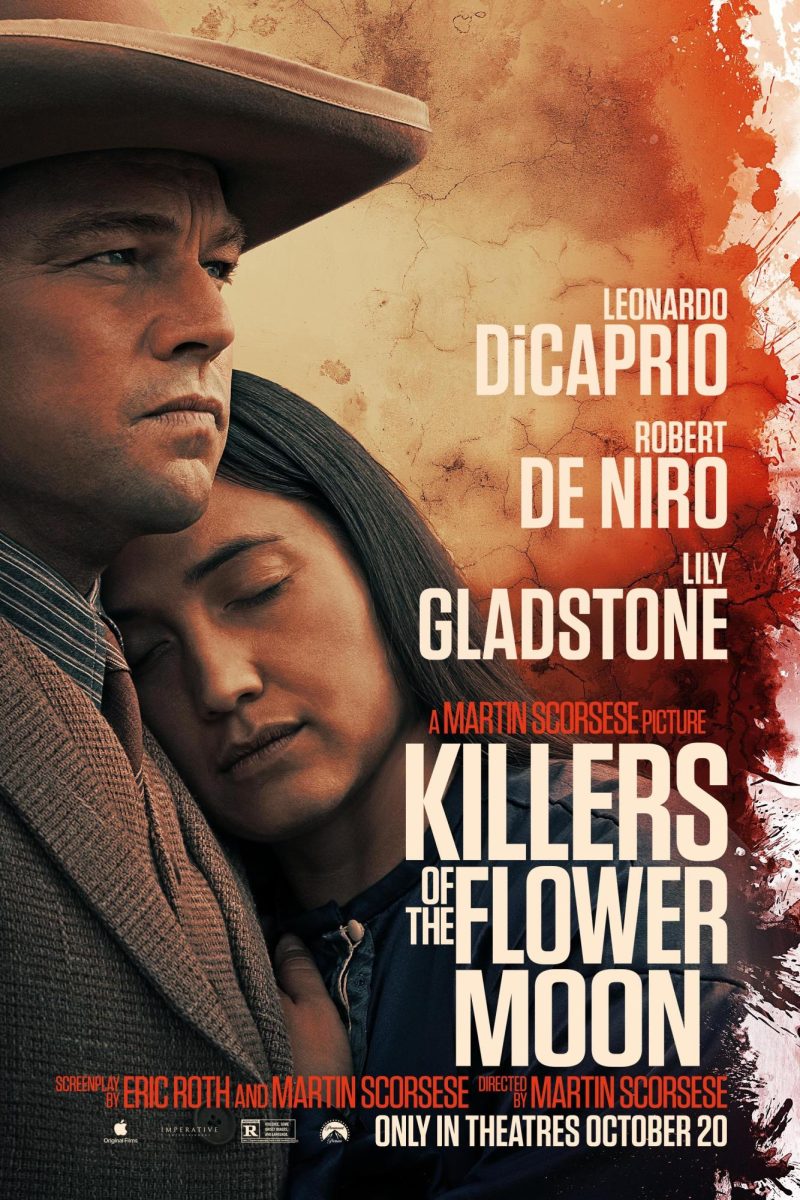

Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” narrating Mollie’s life after meeting Ernest, was released to theaters on October 20 after six years of production. This Western historical drama, based on real events, was notably well-paced and engaging, with an adrenaline-pulsing plot full of evil twists. I found the plot’s smooth progression to be a significant asset, allowing viewers to fully appreciate the many unfolding events and characters, despite the plethora of Williams — William Hale, William Smith, William Hamilton, and so on. It was also one of the truest book-to-film adaptations I’ve seen, encapsulating the vast majority of David Grann’s book by the same name. It struck an impressive balance between a fact-driven storyline and the depth of emotion. This was crucial in encouraging empathy in the audience and allowing them to digest the film’s violence without feeling like they were watching a horror movie.

As for the viewing, the lighting on set was a masterpiece; the scenes often resembled oil paintings, featuring hues of rich greens, blues, and browns and covering the Osage land with a shadowy blur to emphasize the bleakness of cruelty they faced. Period-appropriate scenes added greater depth and context to the plot, drawing from commonly known events, such as the Birmingham bombing, KKK rallies, and the automobile boom. The usage of Osage language, often lasting minutes without transcriptions or translations, enhanced the suspense factor and shifted the audience’s focus to characters’ expressions rather than the words themselves. The language integration was an important goal shared by both the Osage nation and the film’s directors, as it shows the lasting presence the Osage have had and acts as a revival of their language. All lead-role actors learned to speak Osage, including well-known actors Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Lily Gladstone, a member of the Blackfeet Nation who grew up in Seattle.

These subtle yet crucial details can be credited to director Martin Scorsese, a famed Hollywood filmmaker known for his mastery of on-screen violence, who took on the challenge of condensing David Grann’s retelling of the decades-long chase of Osages murders into a single movie. Originally, Scorsese’s screenplay was centered on the adventures of Tom White, the FBI agent in charge of the Osage murder cases. However, after speaking with the Osage nation on their homeland about the white perspective from which they were writing from, former Osage chief Jim Gray recalls: “[Scorsese’s] eyes got really big. And he said, ‘I’ve learned a lot from listening to you all. And I want to take some time to postpone production, to give myself time to write this story right. And I don’t want to start it until I do.’”

After the script was largely rewritten to focus on Molly’s experiences, Scorsese made further arrangements. He paired costume and set designers with Osage hosts to learn how the Osage dressed in the 1920s, what their homes looked like, and the type of food they ate. In fact, some of those designers were Osage artists, craftspeople, painters, and electricians. Every detail, from the way the women wore their blankets to the inflection of the actors’ speech, was weighed in on by an Osage representative. Even the catering contract during the eight months of filming was arranged with a Pawhuska chef. When asked for reaction to the film, former chief Jim Gray says, “The way they shot scenes involving an Osage funeral and Osage weddings, and even the Osage Council meeting, was all done with reverence and accuracy. It didn’t have to go down that way. I know it didn’t. 1920s Osage Nation came to life in this film in a way that I can’t really put into words.”