The initial excitement surrounding artificial intelligence–generated visual art has faded since its emergence in the autumn of 2022 — peaking in Google search interest that December. Technology and creativity merged, making it possible to transform any given prompt into a related visual representation. Excitement abounded as sites granting folks the ability to use AI to generate art began popping up. OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 and Midjourney systems became the faces of this art revolution. However, amid the excitement and innovation, a subtler issue emerged: the biases ingrained in these AI art tools. Only recently has dialogue happened discussing the racial biases in popular AI art platforms — most notably, the whitewashing of black and brown skin in TikTok’s AI-generated anime filter and other filters of its kind. This conundrum prompts us to wonder: How do these biases occur, and what are their consequences?

When given the prompt “woman”, the Midjourney AI’s depiction almost always shows a pale-skinned, brown-eyed, brown-haired, feminine face, even across different art styles (scan the QR code for examples). With no other descriptors in a Midjourney user’s prompt, the result for “woman” rarely varies and, even when it does, never with skin color. Any sort of diversity must be intentionally created via a more specific prompt. Women, to our AI, seem to be synonymous with a singular stereotypical archetype, and it all has to do with AI’s origins in pattern recognition.

According to the U.S. Census, the most common traits in American women are identical to what I’ll call “The AI Girl,” characterized by pale skin, dark eyes, and dark hair. However, The AI Girl encompasses only a singular picture from the vast expanse of phenotypes that all equally define and represent womanhood. So, why does the phenomenon of The AI Girl persist? Well, the basis of AI generation is meeting prompt expectations. To achieve this goal, AI sieves through extensive datasets for patterns, prioritizing what aligns with the desires of the majority of users.

At a cost to accuracy, another approach to AI-generated art is one in which models use a more diversified “randomization” process. Take the prompt “apple.” The user would most likely want to see a rendering of the fruit. But, there are many interpretations of the word apple, and if an AI were to “randomize” its data sets and combine them, we might get a mutant Apple iPhone and apple fruit — an absurd result for a simple prompt. Thus, to get the most “accurate,” visually appealing, and marketable result, AI is built to look for patterns: It asks what is most related to the term prompted. It’s forced to display what is in the majority, but is unable to achieve real accuracy due to its continuity. This trap of repetition not only weeds out the company Apple, but also yellow apples like Opal or Golden Delicious, rotten apples, and all the other forms apples can take that don’t align with that singular amalgamation of majorities — flawless, whole, ripe, and red.

But why should you be concerned? Can’t users simply provide more specific prompts to counteract this bias? Couldn’t we just build diversity through intentionality? Contributing to the excess of white faces in art is what makes the majority bias in Midjourney and DALL-E harmful, rather than just inaccurate. This bias towards pale skin in American and Western art far predates these technologies and is born from a long history of white supremacist ideals. Putting the onus on the user of AI art generators to prevent upholding this oversaturation of whiteness doesn’t recognize pervading human biases and doesn’t give companies like Midjourney much credit. We should expect influential technologies to be prepared for consumption and user needs. As future engineers and leaders, it’s in our hands to construct a norm of a thoughtful and cautious approach to innovation. For tools like these — and the many in our future that will influence society in elaborate, unpredictable ways — our standards must make it unacceptable to rashly release materials that uphold harmful stereotypes. We can do this by encouraging companies to mitigate biases before launching their products, vocalizing concerns, and engaging with businesses/competitors that are being prudent. An example of this intentional approach to AI art is Google’s Imagen, another AI image generator.

Imagen is currently unavailable for public use. On its website, Google cites a variety of reasons for this decision, one of which is that “there is a risk that Imagen has encoded harmful stereotypes and representations,” and it will not be available for public consumption “without further safeguards in place.” Google both recognized AI art platforms’ current biases, and that it will take resources and innovation to advance these tools in a way that eliminates their current issues. Alas, not all AI models aligned with Google’s approach. Consider Midjourney and DALL-E 2, which we now know became prominent publicly accessible generators despite their promoting the erasure of diversity and perpetuation of stereotypes.

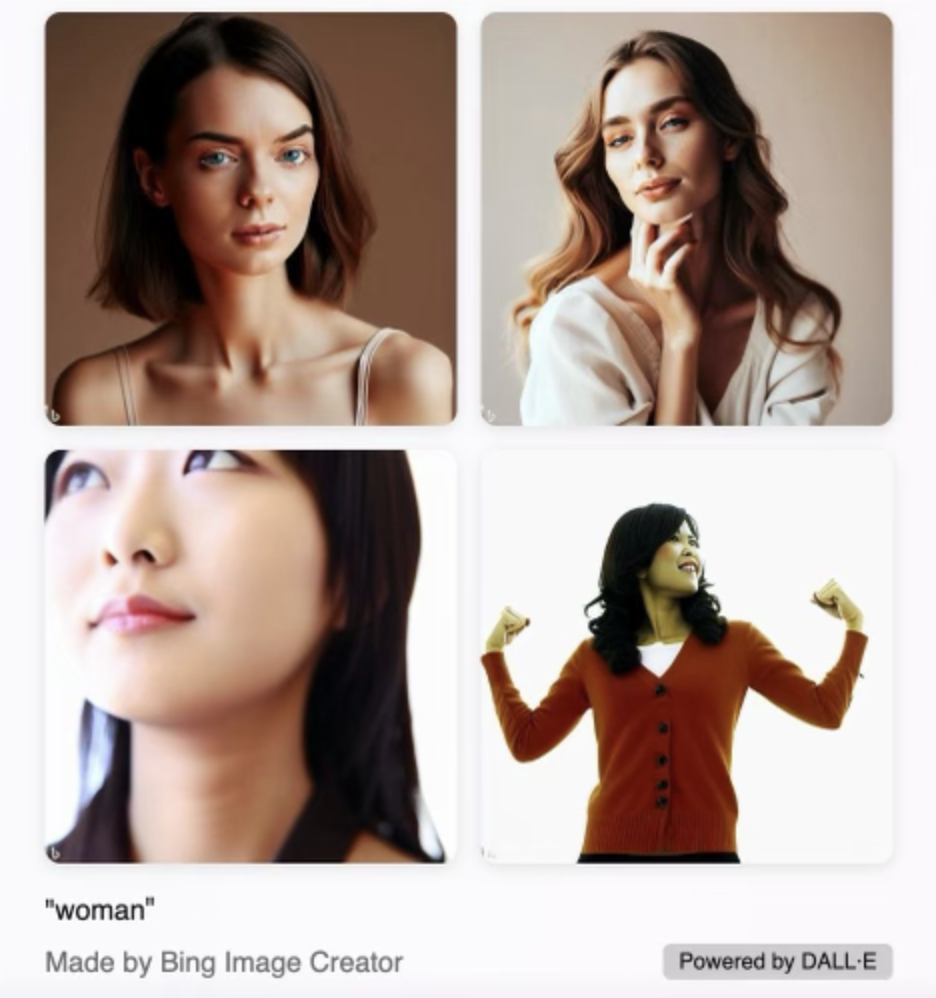

Of course, since this technology went public, some companies have progressed in sharpening their AI. Take, for example, the four images included with this article that were generated by DALL-E 2 using the prompt “woman.” These images displayed slight diversification. However, this progress emerged over time, paralleled by the end of free trials for both DALL-E 2 and Midjourney. What became apparent soon after this change was that the free filters, apps, and websites looking to cash in on a new tech fad were also the least inclined to pour money and time into reducing bias or ridding stereotypes from their generators, making the most accessible AI art generators some of the most shamelessly exemplary of this majority bias.

So, what now? Has the damage been done, forever tainting the world with AI-generated art’s biases? While I cannot entirely quantify the impact of AI-generated art, this article aims to expose a mishandling of AI-generated art and empower you, the reader, to expect more from the future of artificial intelligence. The cautionary tale of this tool’s hindered potential through a risky, premature start should steer us aspiring leaders towards fostering ethical innovation and elevating our expectations for technology. I’ll leave you with this: a system that cannot acknowledge humanity’s diversity in its simplest terms is a system unready for use by the very people it is ill-equipped to depict.