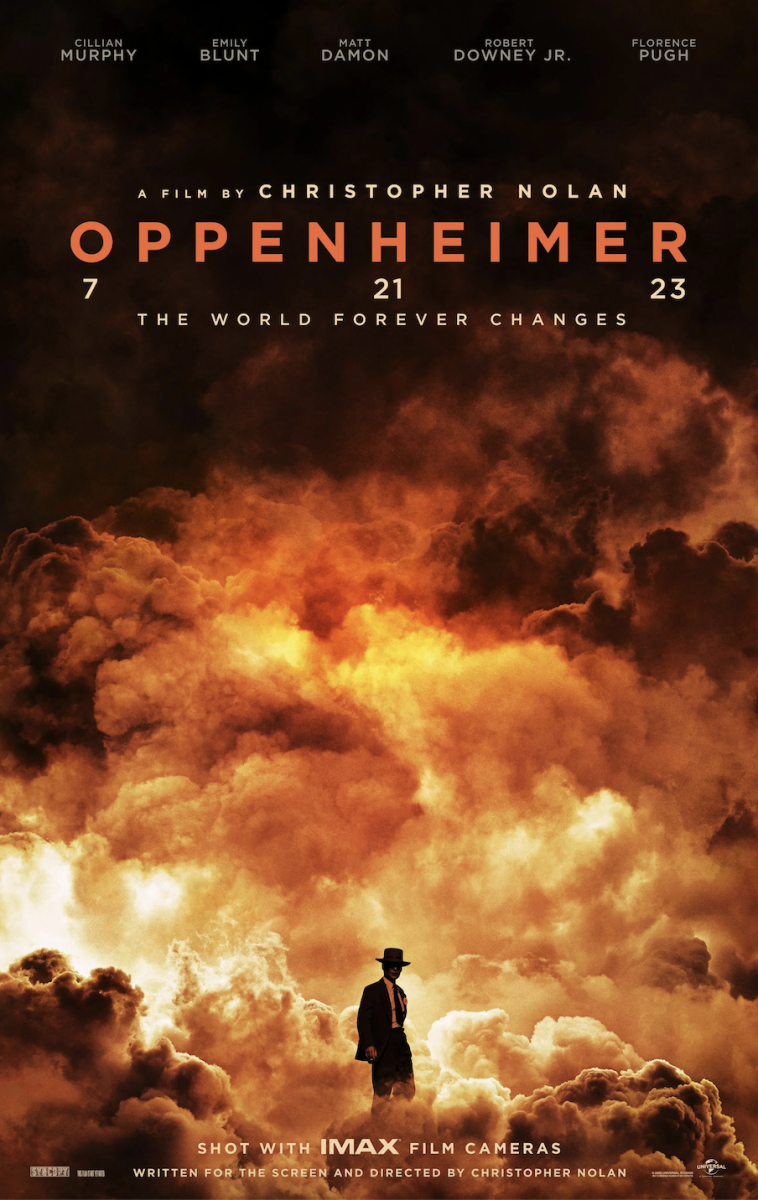

Walking into the theater, I didn’t know what to expect from “Oppenheimer.” From the premise to the casting to the marketing (or lack thereof), everything about the movie seemed equal parts intriguing and contradictory. Was it an authentic biopic or a complete work of fiction? A warning about the horrors of nuclear weaponry, or action-movie agitprop for the U.S. military? In contrast to its bubbly twin film, “Barbie,” which seemingly leaked 90% of its major plot points months before its release, I felt like I really was going in blind with “Oppenheimer.”

Nevertheless, as I walked out of the theater, all my prior reservations were long gone. “Oppenheimer” truly is a work of art, a stunning portrayal of hubris, guilt, and war that kept me on the edge of my seat the entire time. Throughout the movie, Nolan expertly weaves together J. Robert Oppenheimer’s thrilling rise to power and premeditated fall from grace in two deftly framed narratives: “Fusion,” the black-and-white facts of Oppenheimer’s life as recounted by would-be Secretary of Commerce Lewis Strauss, and “Fission,” the view of history as Oppenheimer recalls it, colored by his own biases, memories, and opinions.

As a result, the story is delivered in a series of time jumps, flashbacks, and shifts in perspective, a choice that not only helps the plot of the movie build to a satisfying crescendo (assisted, of course, by Ludwig Göransson’s magnificently atmospheric soundtrack) but makes the three-hour runtime more than justifiable. Rather than dragging on or growing dull with visual and auditory filler, “Oppenheimer” is painstakingly crafted down to the second. Every little sound, sight, and movement has its place, from the opening image of raindrops splattering wet pavement to the removal of a pair of glasses during a particularly tense portion of Oppenheimer’s “trial.”

A small gripe I have with the movie, however, is the veritable Rolodex of side characters foisted upon the viewer. As a result, during certain parts (read: Los Alamos), the storyline is forced to jump erratically from setting to setting and person to person, introducing eminent physicists and crucial allies in scenes that could have been pivotal but instead come across as lackluster and hasty.

And genuinely, the casting choices are just so odd. Rodrick from “Diary of A Wimpy Kid” silently attends a couple of meetings, then vomits next to a bicycle and disappears into the New Mexican night. Josh Peck arrives onstage, sets off a nuclear bomb, and fades once more into the relative anonymity of the background. Peck’s character is none other than the director of the Trinity test, Kenneth Bainbridge, though you would never be able to tell from his near-wordless blip of a performance. And I don’t know about you, but I have never wanted, nor will I ever want, to see Joshua Michael Peck in the middle of a gritty historical biography. It just doesn’t make sense.

Admittedly, there are a few standout performances, like Robert Downey Jr. (whose depiction of Lewis Strauss has led me to begrudgingly admit that maybe, just maybe, Marvel actors can actually act), but for the most part I think it’s safe to say that the star-studded cast was severely underutilized. Florence Pugh, for one, could have benefited from more attention: For a character as essential to Oppenheimer’s story as Jean Tatlock, the movie leaves an astonishing amount of their time together unexplored. Moreover, many of Oppenheimer’s colleagues are given so little screen time that their connections to the project, the field of physics, or Oppenheimer himself are left up to the assumptions of the untrained viewer.

It all boils down to this: I think the movie could have been even longer. Granted, I know that a four- or five-hour-long movie isn’t exactly the most marketable thing in the world, but then again, it didn’t seem like the team at “Oppenheimer” was all too worried about marketing to begin with. And frankly, I’d be more than willing to sacrifice marketability in order to get a more nuanced look at Oppenheimer’s backstory and relationships — not only to see more of the movie’s supremely talented cast, but to better understand the man Nolan himself has dubbed “the most important person who ever lived.”

If there’s one thing I now know about “Oppenheimer,” it’s that the movie gets better with every rewatch. Initially, it was hard not to be annoyed by the film’s portrayal of Oppenheimer as a tragic, principled martyr who just spoke up for what he believed in and was mercilessly punished for it, rather than the morally gray philanderer that history knows him to be. With that being said, I’ve come to realize that that choice was a necessary one. “Oppenheimer” looks favorably upon its titular character because so much of it needs to take place in his own head: The narrative is wholly focused on, and at times, spun by, him. In doing so, the viewers are able to see the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer as it is best delivered: at times jubilant and tragic, at times brilliant and flawed.