“Post-Prevention” and Reflections on the Lockdown

When a hurried faculty member quickly whispered “lockdown” and closed the door to my classroom in Bliss, I, like many other students, didn’t know what to think. Was this a last minute drill of some kind? Were we in some kind of danger? What should we do now? What started as an unexpected interruption to our usual classes evolved into the hour-long lockdown we found ourselves in on the morning of November 8 as a deadly school shooting commenced just a short walk away at Ingraham High School.

Part of the confusion and panic that arose after the hasty announcement of a lockdown was due to the fact that we hadn’t had a lockdown drill yet at the time. Many students and teachers, unsure of what to do, encouraged each other to hide beneath desks and tables and to cover their heads and necks, referring to the earthquake procedure due to lack of other lockdown preparation.

In my class on the second floor of Bliss, students huddled close to the wall and whispered to each other as different accounts with conflicting information poured in, from news broadcasts to firsthand accounts from Ingraham students. However, as time went on, some students began walking around the classroom, talking loudly and walking in front of windows. At one point, a member of the class even ducked out of the classroom into the hallway. Many other students reported loud conversations and walks around the classroom, with one teacher even putting on a movie to ease students. While these activities might have been calming to students, they would have certainly put them at risk had an active shooter been on campus and in buildings.

It was a strange environment to return to after the lockdown had ended. When the assembly was announced, many students, including myself, were expecting for school to be canceled for the rest of the day. However, as Mr. Boccuzzi explained, one of the reasons why school continued was to provide a sense of normalcy and safety to students. While this was a valid explanation, most teachers’ sense of this “normalcy” was pretending like the previous few hours had never happened. Right after the assembly, I returned to a history class that explored the trauma sustained by soldiers during World War I — an important topic, but after a day of such emotional turmoil, it was a hard class to sit through. In the next few days, only one of my teachers truly gave the class to discuss what had happened.

Later in the year, an official lockdown drill was held (albeit a few months after the original incident), teaching students the proper steps to take if we ever find ourselves in one again. While this was a definite step in the right direction, this reflects a trend in Lakeside administration of taking preventative action only after an incident has already happened. A similar case of “post-prevention” occurred last year with the assembly on sexual violence prevention, which only took place after rumors of an incident involving members of the football team group chat had started to spread through the school. Though it should have been an event prioritized at the beginning of the year, it only came to be once students had a reason to look to sexual violence prevention policies.

The lockdown and sexual violence assemblies point to a greater trend in Lakeside’s administration, where things just take time. Ideas such as instituting a land acknowledgement and removing the tombstone have been discussed for years, but meetings and concerns are prioritized over taking action, which leads to poor handling of events like the lockdown.

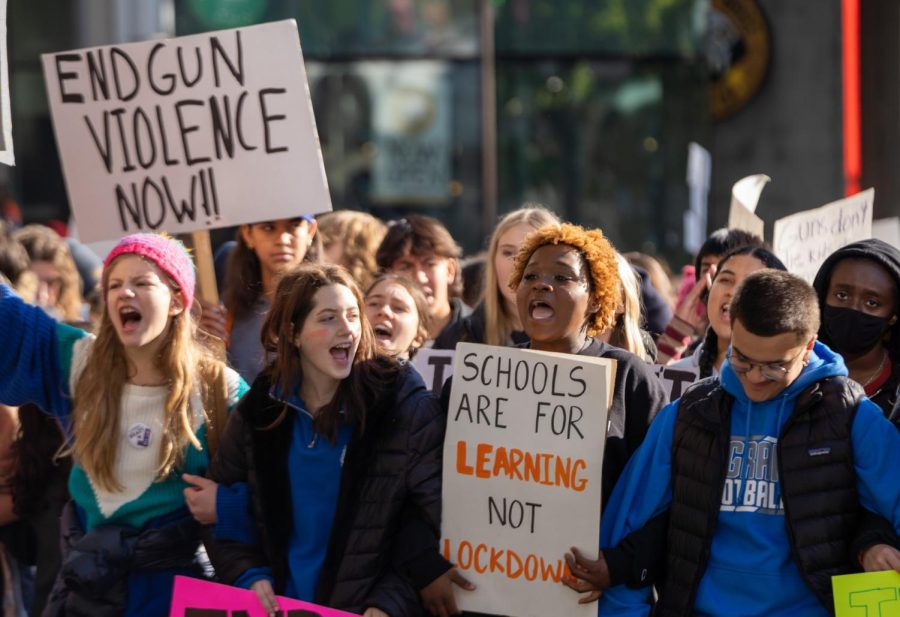

This trend of inertia continued as students from Seattle schools prepared for the November 14 walk-out and protest against school shootings and gun violence. As I talked with students as the day of the protest drew closer, many shared that they would have attended had the absence been excused or a test not been planned for that day. Additionally, an unexcused absence meant that students couldn’t attend any Lakeside activities after school — especially detrimental given that sports practices, including winter basketball tryouts, were happening that week. After hearing multiple accounts of school events making it infeasible for students to protest, Lorelei S. ’25 and I decided to approach Mr. Boccuzzi and ask about this policy on unexcused absences, and if it could be amended.

When asked about the worries surrounding the attendance policy for the protest, Mr. Boccuzzi politely stated that it wouldn’t be changing. He noted that the whole point of the walkout and protest was to go against the status quo, and if the school let students go to the protest with an excused absence, our actions wouldn’t hold as much weight as before. While this is true, the students were protesting the system and policies in place that lead to school shootings, not the school’s attendance policy. In allowing an exception for this purpose, Lakeside would’ve been showing their support for the students who had been affected by such shootings in the past, rather than centering the attention on their attendance policy for students considering supporting the cause. This would’ve been suitable after the lockdown and subsequent school days didn’t run as smoothly as expected. Additionally, Seattle public schools, including Ingraham, have a policy that excuses students for one day every semester for civil disobedience.

Despite these missteps, the school still supported students in some ways; they set up tables before the walkout, so that students leaving campus did not have to navigate to the student center to sign out. Lakeside students are supported, in ways some don’t even realize; what we need now is to openly communicate with administration about our concerns, and for action to be taken swiftly.

Lael is disillusioned.

Born May 29th, the universe stopped when Lael entered the world. Per her own recollection (which is “super sharp”),...