Day in the Life of a Nationally Ranked Fencer

Fencing — an organized sport involving the use of a sword épée, foil, or saber — is a unique sport that requires fine technique, tactics, and coordination. I wouldn’t call myself the modern-day Inigo Montoya by any standard; nonetheless, I’m here to tell you there’s more to the sport than the flashy spin moves in The Princess Bride.

In October, I traveled to USA Fencing’s first North American Cup of the year in Minneapolis to face some nasty competition. Unlike other events of its kind, this tournament invited only the upper echelon of U.S. fencers, Division 1, and was probably the most stacked U.S. tournament in years. It featured around 200 total fencers, including all of the U.S. Olympic Team members, multiple international fencers, world medalists, and all of the top college fencers as well. With this in mind, I needed to arrive a whole day before to get proper rest for the challenges I knew I’d face.

The next day, I slept in comfortably until 9 a.m., then walked down to the hotel lobby to enjoy a healthy plate of eggs, bacon, and toast. Compared to a typical 8 a.m. start, this brief leisure felt like luxury. After breakfast, I changed, packed my equipment and rode the skybridge to the competition hall. Once there, I scoured the massive arena for a space to warm up with my teammates and get ready for pools.

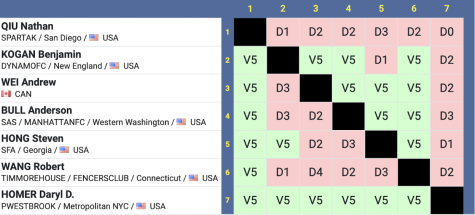

All tournaments are divided into two rounds: pools, which create seeding in the tableau, and Direction Eliminations (DEs). Pools are first to five touches, whereas DEs are 15-touch bouts. In an unfortunate twist, I was sorted into the most competitive pool with the likes of Olympic silver medalist Daryl Homer. Despite his impressive Olympic silver medal resume, I put up a strong fight. After falling quickly down 0-2, I rallied back with two flying attacks to even the score. After missing a golden opportunity to score a third straight attack, Homer took the lead 3-2, but I once again bounced back to even the score. After a questionable call from the referee, Homer once again took the lead, and kept it, winning 5-3. With the loss, I finished pools with three wins and three losses to be seeded slightly above the middle of the pack.

After the bout, I had just 15 minutes to get ready for another round of DEs while the officials checked to make sure all scores were reported correctly. Even a difference of one point would have a drastic effect on who I’d fence next. Once the tableau was posted, fencers waited for a referee to call them on one of the four strips in the pod. I had a solid first DE, winning 15-8. Once a fencer wins a DE, they bring a slip of paper confirming their victory to a committee, who then assigns a matchup for the next round. As I walked back to my pod with a new slip in hand, I glimpsed my next opponent — Luke Linder, who, standing at 6’4”, is the 2021 NCAA individual champion, a Cadet and Junior World Team Member, and a multiple time National Champion. All that is to say, he’s the best college fencer right now. I fought hard but ultimately took the loss; while I am one of the faster fencers out there, I couldn’t keep up with his deadly combination of speed and size.

Regardless of the loss, I showed massive improvement from last year and this was a great tournament to start off the season. My next North American Cup isn’t until December, but stay tuned for fencing video content in a future issue to experience high-level swordplay firsthand.