Tatler: School Paper or Student Paper?

“Tatler Doomed to Obscurity.” “What has Journalism Become?” “Tatler must protect freedom of speech.” “Administration Should Think Twice Before Censoring”—just a handful amidst heaps, these Tatler headlines from the late ’80s to mid-’90s are quick glimpses into a former Tatler intent on fulfilling its role as the student press: delivering accurate and relevant information to the student body. But is Tatler still a student paper, or has it become a school paper?

Several students shared their responses to the question: “Because there’s adults involved, I see it as a school paper.” “It’s a student paper. Even though it covers school events and topics, it’s still written from the student perspective.” “I think [Tatler has] to have [the administration] proof read everything, but they won’t directly edit your stuff.” “I thought the adults were the ones who cumulated [the content] and put it in the paper.” “[Lakeside] culture is ‘Don’t be controversial.’” Current editor-in-chief (EIC) Haley Z. ’22 adds, “There is definitely a perception among the student body that the administration censors Tatler. I get a lot of comments about how we’re ‘just PR’ for the administration.”

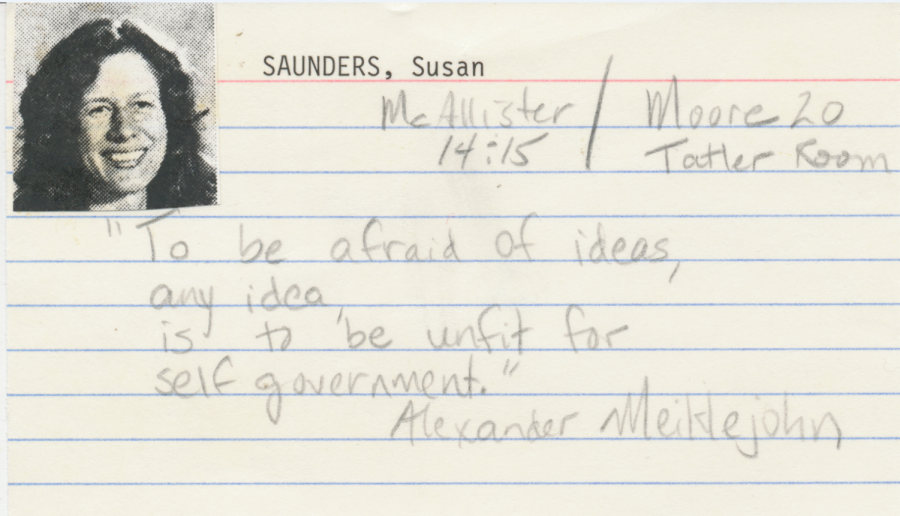

Although many of these thoughts are misconceptions today, in past years of Tatler, they would’ve proved to be absolutely untrue. According to former EIC Natasha Shulman ’89, past Lakeside teacher and paper faculty advisor Susan Saunders is “key to understanding [the ’80s to 2000s] of Tatler.” While writing a Ph.D. dissertation on first amendment rights, Saunders joined the paper in 1985 only after she’d made her role abundantly clear: “I had no interest in serving as a censor for the school,” Saunders says. “The advisor at the time explained the system to me. Three people voted on every issue of concern… [The two] editors-in-chief could vote out the advisor. … Once I heard this, I was in.”

Though appreciative of the voting system’s sentiment, Saunders did not continue the practice as advisor. Instead, she began to lead discussions where no one had a vote, effectively giving herself less power and communication more power. Last year’s EICs, Anya Shukla ’21 and Vincent Wilson ’21, note that it is the same method today. Wilson observes: “We probably had as much freedom to cover what we wanted as any previous EICs.”

So why do some Lakesiders believe that adults are involved in Tatler or have the final say—that the paper is published for the school instead of the students?

In the past, Lakeside recognized the importance of journalistic education with three different curricula: a Journalism class, a First Amendment class, and Tatler. All three were led by Saunders, and she even introduced the First Amendment class herself: “If it were up to me, every Lakesider, every high school student in America, every citizen in our democracy would be educated on the nuances and complexities of the First Amendment.” Saunders taught all her classes, including Tatler, with the principal, “Real responsibility is a great place to learn,” in mind. In fact, Saunders believes Lakeside’s biggest success stories can be credited to the freedom and trust the administration gave to its students. She references Bill Gates ’73 and Paul Allen ’71: “They spent their summer creating the student schedules for the next academic year! Their curiosity about the new technology was encouraged by [former Head of School] Mr. Ayrault who handed over to them real responsibility.”

Saunders’ dedication to teaching students life lessons was evidently impactful. One of Saunders’ former students, former EIC Martha Brockenbrough ’88, also advised Tatler. Brokenbrough is now a successful author, and in her book, Unpresidented, she writes: “To Susan Saunders, who started me on this path.”

Along with Saunders, Brockenbrough seconds the importance of students making decisions on their own. Invited to fill in for Saunders during her leave from 1992 to 1993, Brockenbrough continued to advocate for student decision-making on the paper: “Nothing was off the table.” Unfortunately, the same sentiment was not shared by administrators of the time such as Head of School Terry Macaluso. In one instance, one of Brockenbrough’s students, Chris Miller ’93, critiqued the lack of administrative visibility with a “Where’s Terry?” parody of “Where’s Waldo?”. Coupled with several other encounters with the administration, Macaluso quickly assured Brockenbrough that she would not be asked back once Saunders returned. Meanwhile, Miller went on to a career in Hollywood and produced renowned titles like The Lego Movie and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. “Had he not had the freedom to do his comedy, what might his career have been?” Brockenbrough wonders.

She also recalls being a staff writer: “My friends and I used to say, ‘When my real life begins…’ and what we meant by that is after we’re done with school, somehow our real lives would be beginning. What Tatler gave me was a jumpstart to my real life. It was one where I got to make decisions.”

In one instance of “real life,” Saunders describes a day with “teachers and staff members in heated discussion and sticking sticky notes on the walls, some reflecting outrage and others in support of what had appeared in Tatler that morning.” Weeks earlier, Tatler writers had interviewed Numidian advisor Dale Bauer on the controversial announcement to start censoring the long-time Numidian tradition of senior pages. During the interview, reporters were shown the unpublished quotes that students had submitted: “The question of whether or not to print some of the more heinous quotes [in Tatler] was tough,” Saunders says. However, the decision was fully in the hands of the students. Despite predictable backlash, Tatler EICs at the time, Alice Ho ’91 and Charlie Meredith ’91, pursued the project as they “felt that [the community] wouldn’t have a realistic understanding of what they were advocating or opposing.”

Reflecting on the situation, Saunders goes on: “Some were sure to complain about ‘rebellious editors’ ‘sticking a finger in the eyes’ of the adults. Some would likely see it as … ‘sticking it to the man’ …” But she disagrees with both: “The reporters and editors weren’t trying to rebel against anything. They were trying to report on a complicated issue.”

Saunders goes on: “I have been astonished by how quickly some adults who would sing the praises of those ‘responsible’ students before they were editors, quickly reclassified them when upset about something the students published. … We don’t want to send citizens out into the world who show obedience to those in power without keeping their critical eyes to what they are being asked to be obedient.”

In February 1991, just months before the issue including Numidian quotes, Tatler staff ran into another problem with the administration. Acting Head of School Frank Magusin planned to ask the board of trustees to approve a policy that would restrict religious-affiliated content in Tatler advertisements. In reaction, a reporter wrote, “Editor-in-Chief Alice Ho is ‘outraged’ … [C]o-editor Charlie Meredith was upset… The editors should be able to create as diverse and open a paper as possible. That doesn’t mean that if the Ku Klux Klan came and asked to advertise they would be allowed to. It means that the editors should make that decision.”

Two months later, in April, another reporter declared: “After thorough discussion of the issue with representatives of the paper’s staff, Magusin did not go forward” with the policy. “In doing so, Magusin demonstrated an admirable quality … He decided that [the students’] newspaper should be just that: [the students’] newspaper—not the administration’s.”

However, once Brockenbrough was ironically brought back to advise Tatler in 2004, she saw that the administration had lost trust in Tatler’s approach.“We would prefer that you have the last say on everything in the paper,” Brockenbrough recalls administrators saying. She sighs: “There aren’t that many subjects that you can teach that way to students.… Lakeside had about one of the best programs in the nation.” Additionally, in Brockenbrough’s return as Tatler advisor, she felt the position had suffered a large increase in work though the percentage of a full-time contract alloted to advising Tatler decreased—the newspaper was “not valued, not seen as an educational necessity.”

On the one occasion where Brockenbrough agreed to censor writers, she omitted a line of an article detailing a fired teacher’s nonsexual inappropriate conduct with students—the line said that the teacher would “miss the students.” Brockenbrough remembers her admission to the administration as a mistake—later on, she found out that one of the students involved was incredibly upset about the teacher leaving and would have benefited from hearing the quote. “I shouldn’t have done it,” Brockenbrough says.

She goes on: “The assistant head of school told me that if we printed another article, that it would harm the school community. I said, ‘If everything is accurate in that article, you think it’s [going to] harm the community?’ She said yes. … I said, ‘I disagree.’ … The idea that speaking the truth is harmful is one that I reject forcefully.”

Saunders officially departed Lakeside in 2005. Brockenbrough followed suit, leaving Lakeside halfway through the school year in 2006: “I didn’t feel supported by the administration,” she explained. When the school faced diversity lawsuits in 2007, the Seattle Weekly paraphrased Saunders in an article concerning the subject: “The school has lost its appreciation for dissent.”

Today, Tatler exists within a different world: the paper is published online in addition to print, parents read it regularly (due to issues being mailed to home addresses during remote learning), the administration has become more self-aware of how they’re perceived, and Lakeside’s nation-wide prestige and reputation have risen significantly. The paper’s increased access and attention from non-Lakeside students has made it more difficult for writers to write controversial stories—not for the risk of censorship, but for the fear of inaccuracy. Wilson says, “Even though we do self-censor, it’s always because we’re worried we’re wrong about something … It’s not that we’re worried we’re right about something and the administration will do something about it.”

Last year, students in Tatler’s class of ’21 wrote an open letter to the administration, discussing the issue of sexual assault at Lakeside. The letter was triggered by a high profile case already circulating on social media, and the article was first distributed to seniors before being published in the paper “for maximum effect… We intentionally wanted to get the article out at a specific time to get an impact on the students, so we chose to not get a statement,” Shukla says. This time gap between the first and second issue of the letter, however, lent time for the administration to write a response for the issue in the paper.

Shukla shares, “After we published [the first issue], the administration ended up having a meeting with us. … We thought they were going to get really mad, tear our entire article apart, and say we can’t write anymore. But that’s actually not what happened. From my recollection, they didn’t have any comments about what we wrote, they just wanted to know about the issue behind it. … The fear of censorship was in our heads…”

Haley comments that Tatler advisor Mr. Collins “was very supportive” about last year’s letter to the administration. She, however, believes that he “does tend to sympathize more with the [administration] in general.” In one example, Haley explains, “He wants us to consider renaming Angry Lion [to something] like Honest Lion because the [administration] perceives it as ‘too negative’ …”

This year, another controversy arose involving student sexual harassment at Lakeside. Shortly after the controversy, in a Tatler brainstorming meeting, Haley recalls Mr. Collins being surprised that no one wanted to write about it: “[Managing Editor Ann H. ’22, Co-EIC Evie BW. ’22], and I all hadn’t even considered it—it seemed sort of outside what we were allowed to [publish].” She continues: “I’m not sure if we thought we would get in trouble or if we were worried about respecting the victim’s wishes—probably some of both. There were all kinds of rumors going around the school, and it probably would’ve been a public good to clear things up and publish the facts.”

Mr. Collins states, “I can say there is no administration censorship affecting Tatler now, though there occasionally is some tension after issues have come out.” With this tension and the potential for it, some students believe that Tatler staff writers approach topics subtly, cautiously, or not at all—a perhaps appropriate response to a student-described “Don’t be controversial” culture. As an example, one student expressed their frustrations with their criticisms on a school event being “watered down” in the published interview.

“We have a really high burden of proof to get things right,” Haley explains. “I want to make Tatler a bit bolder … but it’s actually really hard to be controversial in a responsible way. … I don’t think that’s self-censorship, just good journalism.”

Evie continues: “There’s been a shift in how Tatler views its role within the community.” As a result of COVID, she says, “We now feel that our primary responsibility is to promote unity. I do think it’s an issue … that we’ve somewhat lost sight of our role as the press: to present unbiased information on what’s relevant—controversies and critiques included. My hope is that in my final few months as an EIC, we will rectify this.”

Today, Saunders still maintains that “the more authentic responsibility students can experience, the more they are prepared for responsibilities as adults in our society.” She continues: “The ultimate responsibility of a free press—to confront and question those who hold power in a community and to find out how they are using that power to serve their community. If Tatler doesn’t do this work, who will?”

Today is gonna be the day that we talk about Estelle Lee,

She's the managing editor, planting the journalism seed.

I'm sure you've heard her name,...